.

Mahnaz never really felt like Afghanistan was her home.

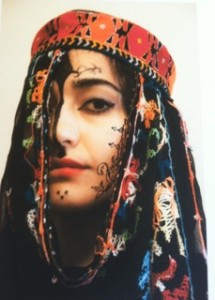

“My mother always told me about Afghanistan, about my aunts. I heard them but I couldn’t feel them.” During Afghanistan’s occupation by the Soviet Union between 1979 and 1989, the Afghan army conscripted eligible young men to suppress the anticommunist mujahideen. Drafted once already, her father sought to escape. In 1983 he moved from the Afghan city of Herat across the border into Iran. Later, Mahnaz’s mother and two of her siblings joined him. Mahnaz and three of her five siblings were born and raised in Iran. But in 1994, they came back to Afghanistan. Mahnaz was seven. After six months, the Taliban came. “At first, people thought the Taliban would be better,” Mahnaz tells me. Ismail Khan, who governed the province between 1992 and 2005, was patently corrupt. The people of Herat were optimistic that the new leadership would be an improvement. “But after a few months, the Taliban started torturing people,” she tells me. “Like, beating men to go to prayer. Closing all the schools for girls, and all the public bathrooms for women.” The Taliban targeted the Shia population, sending threats to individuals and families. “Everything got suddenly very difficult for Afghan people. And they saw the true face of a devil.” Mahnaz is Shia. But unlike the case for some Shiites from the Hazara ethnic group, her religion can’t be easily identified based on her facial features. But Mahnaz’s neighbors, Shia Hazaras, did not have the same fortune. “A group of armed men, they attacked their house, and stole everything they had. They told the parents, ‘we will come back for your daughter, and we will take your daughter.’ The morning after, they were screaming. And everybody could hear the screams. But nobody went to help them. Nobody could go to help them, because there were armed men. During that time, my father and other neighbors, they were sleeping on the roof so they could guard the houses.” The Rezaies also received direct threats from the Taliban. “Yeah, there was a lot of threats against everybody. Especially Shias. Because, in provinces like Bamyan and Mazar-i-Sharif, they killed—they would behead all the Shias.” After two and a half years living under the Taliban’s shadow, the Rezaie family decided, again, that they had to leave Afghanistan. So they went back to Iran. Strange Homecoming When Mahnaz’s family left Afghanistan for the second time, they weren’t alone. The Soviet-Afghan War forced more than 5.5 million Afghan refugees to flee to Iran and Pakistan. “There was a big, big line of Afghans trying to go back to Iran. But they couldn’t.” The heavy influx of refugees strained the country, arousing discrimination towards Afghans that made it difficult to live a normal life. At the time, her brother worked for an American NGO which helped her family obtain visas. Suffering from an ongoing illness, her mother needed critical medical care that she could not access in Herat. “A miracle happened,” Mahnaz tells me, “and we got the visa and we went to Iran.” But Mahnaz describes Iran’s attitude towards waves of Afghan refugees as “very discriminatory.” “They were helping them, they were giving them identification cards and everything. But after Khomeini died, and the other people came – Khamenei and others – they started to cut benefits and restrict all the Afghans…because it’s all about the politics.” Before the Rezaies left Iran, Mahnaz’s father built skyscrapers as an architect. When they returned in 1999, it was much more difficult for Afghan refugees to find employment. Some Iranians thought Afghan refugees were taking their jobs. But Mahnaz points out that most refugees took labor jobs. Employers were encouraged not to hire Afghans. In some cases, it was considered illegal to do so. “It’s kind of like the situation of Mexicans in the United States,” she says. Her father’s former boss gave him a break, and he landed a position as a construction supervisor. Employed illegally, he was paid minimum wage, far less than Iranians working the same job. “In Iran, the second time, it was really hard for me. I got the feeling that this wasn’t my country,” Mahnaz recalls. After 1979, following the Iranian Revolution, the country allowed children with proper refugee documentation to receive free education. “But still, some people weren’t happy. So the government brought lots of changes.” In 1997, the Iranian government introduced new sets of refugee laws that UNESCO says were designed to restrict the number of Afghan children in publicly funded schools. If a child wanted to attend school outside of the region where they received documentation as a refugee, they needed a travel permit. These permits had to be renewed four times a year, at a cost. In some cases, refugees could only register for schools in residential areas designated for Afghans. Unlike Iranian identification cards, those for Afghan refugees restricted them from traveling internationally, and buying a house or a car. The Right to Learn Without proper documentation, Mahnaz could not attend the Iranian school in her area. Instead, she had to pay additional school fees and attend a private Afghan school, which only taught children up until the fifth grade. To catch up on the years of school she missed when her family lived in Afghanistan, Mahnaz took classes during the summer as well. After completing elementary school, she applied again to enroll in an Iranian school. She was denied at first, but found a spot in the program’s night classes. During the school day, Mahnaz’s school officials harassed her and other Afghan students to pay tuition. “They were saying like, ‘you need to pay because you are Afghan.’ They would take out students during the class and like, kind of shame them in front of all the other students and telling them, ‘Oh you are Afghan, you need to come out and you need to pay.’ It was really hard.” Mahnaz’s family was struggling. Alone, her father worked to pay rent, support her sick mother and her five brothers and sisters, and pay their school tuition, all on a minimum wage. She feared she would have to stop going to school. Her school Principal knew she and her cousin were struggling, and found a way to pay their school fees. Mahnaz remembers what her Principal told her. “I know you are really hard-working people, and the way that our government is treating you is not right.” Life After the Taliban When it was time for Mahnaz to enter high school, she was told that she was no longer eligible to receive an education at Iranian schools. “Iran’s government came up with new policies every year. While Iranian kids could register early, Afghans had to wait for the Ministry of Education’s permission for months.” For the third time, her family felt they had no choice but to seek home elsewhere. Mahnaz’s brother and sister were still living in Afghanistan. Her brother, Rasoul, had a stable job with Catholic Relief Services, and he offered to support the family if they could manage to return. Facing growing discrimination, and with no possibility of further schooling for Mahnaz or her sisters, the Rezaies went back to Afghanistan in 2002. By that time, the United States had invaded Afghanistan and the Taliban had left Herat, scattering to other provinces. The community was still plagued by insecurity, so Rasoul encouraged Mahnaz to wear a burqa for protection. She had just started a job teaching English in a region where six years earlier, the Taliban stopped allowing education for girls. Rasoul’s mother-in-law insisted that Mahnaz and her sisters cover themselves, arguing, “they are beautiful, and people will kidnap them and kill them.” Rasoul got another job in Kabul, and the family moved. Mahnaz eventually found another job teaching English. In the years to come, she would work for the International Medical Corps, the Louis Berger Group, an American civil engineering company, and International Relief & Development. An American Life In 2007, Mahnaz came to the United States for the first time with an educational exchange program through the American Councils in Kabul. She and another young woman from Afghanistan stayed with a family in Knoxville, Iowa. At a party with the host family, a guest took out her cell phone and asked Mahnaz if she knew what it was. Mahnaz replied, “yeah, I know, because I have the same one in my purse.” “I got to eliminate some of my stereotypes about America — I didn’t know what America was — and then those students and people that I met in Iowa, after they got to know me and I told them my story, they got to see me and understand some of their own stereotypes, and how they were wrong about some of the things that they thought.” An American School When she returned to Afghanistan, she continued working in Kabul as a document control specialist for International Relief & Development, while starting her degree at the American University in Kabul. Her goal was to pursue a bachelor’s degree in the United States. A peer suggested that Mahnaz enroll in an online writing class for Afghan students hosted by Professor Hector Vila at Middlebury College in Vermont. Eventually, Vila encouraged her to apply to Middlebury, and she received a full four-year scholarship. Attending an American university challenged her. Growing up, she was used to what she describes as the “conservative environments” of Iran and Afghanistan. “I was very conscious not to make eye contact and other things. During the time I was in Kabul, I was wearing a long black veil. So when I came to the United States, I was wearing like, long coats and scarves, and I wasn’t shaking hands. It seems that when I was in my own culture, everything was—I kind of believed in that culture. And many things became invisible for me. I wasn’t seeing them. But when I traveled to the United States I saw much of the discrimination that women face in Afghanistan, but we don’t notice, we don’t recognize it. We think it’s natural.” Water for Herat After her freshman year, Mahnaz received a $10,000 grant through the college’s Davis Projects for Peace. Her project would bring clean water to people in a village in her home province of Herat. Her father helped her to build five hand-pumped wells, which they installed in four mosques and on a piece of privately donated land. After Mahnaz completed the project and returned to Middlebury, she received news that the Taliban had kidnapped the man who donated land for one of the wells. According to people in the villages where the wells were installed, the Taliban came asking about Mahnaz, “the girl who came from America and brought money.” Her father received a letter threatening them, her brothers, and herself. “When they sent the letter to my house they said, ‘we know that your boys are working with American NGOs, working with infidels. We know that your girls are in America, they came here.’ After that, everything got worse in Afghanistan for my family.” Her father moved the family again from Herat, to Kabul. And she started her application for asylum in the United States. “I got my green card two or three weeks ago.” Finding a Safe Haven For Mahnaz, the asylum process was easy. “Everybody says that I’m very lucky.” Three months after she filed her case, she was called for an interview. A week later, she was approved for asylum status. A week after that, she received a work permit. She waited a year to apply for her green card, and received it two months after that. Her sister, who applied for asylum at the same time, has been waiting two years for her initial interview. A friend who applied before them is still waiting. The New Immigrants Mahnaz is now in her second year of study at George Washington University’s Corcoran School of the Arts and Design. She’s pursuing a Master’s degree in New Media Photojournalism. She lives in Virginia with her husband. For her thesis, she’s making a documentary on Afghan immigrants. The project profiles people who entered the United States through the State Department’s Special Immigrant Visa (SIV) Program, which allows special issuance of visas to Afghan nationals who were employed by, or on behalf of the U.S. government in Afghanistan, or who served U.S. military personnel in NATO’s International Security Assistance Force. “Their lives are in danger in Afghanistan. And when they come here, they are given minimal benefits.” Mahnaz says the biggest challenge facing Afghans on SIVs is that they receive no help finding a job. “So they are struggling. But they come here, they don’t know the system, they don’t know how to find their way, they don’t know how to take transportation. Everything is new to them. Suddenly they face a culture where everything is new to them. Even like, crossing the streets. I can’t imagine, if legal immigrants face this many problems, how many problems face illegal immigrants? The people who come here, the majority, especially people who come from war zones, countries like Afghanistan or Syria, they come from very dangerous situations. From very unsafe situations. And they come to this country so they can have a future. And when you hear politicians, like Donald Trump says ‘Oh, they can’t come. We need to send them back,’ or these things, it’s very disappointing. Because he doesn’t understand. He hasn’t walked in the shoes of an immigrant. He hasn’t lost his child in the sea in Turkey. So he doesn’t understand. He lived a luxury life. So he doesn’t understand what immigrants go through.” Supporting Afghan Voices Mahnaz is also a poet. Since 2010, she’s been a mentor and English teacher for female students who are part of the Afghan Women’s Writing Project (AWWP), an online magazine featuring writing by Afghan women. Masha Hamilton, a journalist, author and literacy advocate, started the Project in 2009. The students participate in online writing workshops, giving them tools that empower them to find their voices and share their experiences of life in Afghanistan. The students submit their pieces online, and Mahnaz edits them and gives feedback. She also produces original poems and personal narratives for the AWWP website. “I write about my time in Afghanistan, living during the Taliban.” You can find her work at www.awwproject.org.The views presented in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of any other organization.

a global affairs media network

To Be An American: Twice a Refugee

An officer onboard a Greek coastguard boat talks to Syrian refugees on a dinghy drifting in the Aegean after its motor broke down off Kos. Yannis Behrakis/Reuters

|

February 19, 2016

Mahnaz never really felt like Afghanistan was her home.

“My mother always told me about Afghanistan, about my aunts. I heard them but I couldn’t feel them.” During Afghanistan’s occupation by the Soviet Union between 1979 and 1989, the Afghan army conscripted eligible young men to suppress the anticommunist mujahideen. Drafted once already, her father sought to escape. In 1983 he moved from the Afghan city of Herat across the border into Iran. Later, Mahnaz’s mother and two of her siblings joined him. Mahnaz and three of her five siblings were born and raised in Iran. But in 1994, they came back to Afghanistan. Mahnaz was seven. After six months, the Taliban came. “At first, people thought the Taliban would be better,” Mahnaz tells me. Ismail Khan, who governed the province between 1992 and 2005, was patently corrupt. The people of Herat were optimistic that the new leadership would be an improvement. “But after a few months, the Taliban started torturing people,” she tells me. “Like, beating men to go to prayer. Closing all the schools for girls, and all the public bathrooms for women.” The Taliban targeted the Shia population, sending threats to individuals and families. “Everything got suddenly very difficult for Afghan people. And they saw the true face of a devil.” Mahnaz is Shia. But unlike the case for some Shiites from the Hazara ethnic group, her religion can’t be easily identified based on her facial features. But Mahnaz’s neighbors, Shia Hazaras, did not have the same fortune. “A group of armed men, they attacked their house, and stole everything they had. They told the parents, ‘we will come back for your daughter, and we will take your daughter.’ The morning after, they were screaming. And everybody could hear the screams. But nobody went to help them. Nobody could go to help them, because there were armed men. During that time, my father and other neighbors, they were sleeping on the roof so they could guard the houses.” The Rezaies also received direct threats from the Taliban. “Yeah, there was a lot of threats against everybody. Especially Shias. Because, in provinces like Bamyan and Mazar-i-Sharif, they killed—they would behead all the Shias.” After two and a half years living under the Taliban’s shadow, the Rezaie family decided, again, that they had to leave Afghanistan. So they went back to Iran. Strange Homecoming When Mahnaz’s family left Afghanistan for the second time, they weren’t alone. The Soviet-Afghan War forced more than 5.5 million Afghan refugees to flee to Iran and Pakistan. “There was a big, big line of Afghans trying to go back to Iran. But they couldn’t.” The heavy influx of refugees strained the country, arousing discrimination towards Afghans that made it difficult to live a normal life. At the time, her brother worked for an American NGO which helped her family obtain visas. Suffering from an ongoing illness, her mother needed critical medical care that she could not access in Herat. “A miracle happened,” Mahnaz tells me, “and we got the visa and we went to Iran.” But Mahnaz describes Iran’s attitude towards waves of Afghan refugees as “very discriminatory.” “They were helping them, they were giving them identification cards and everything. But after Khomeini died, and the other people came – Khamenei and others – they started to cut benefits and restrict all the Afghans…because it’s all about the politics.” Before the Rezaies left Iran, Mahnaz’s father built skyscrapers as an architect. When they returned in 1999, it was much more difficult for Afghan refugees to find employment. Some Iranians thought Afghan refugees were taking their jobs. But Mahnaz points out that most refugees took labor jobs. Employers were encouraged not to hire Afghans. In some cases, it was considered illegal to do so. “It’s kind of like the situation of Mexicans in the United States,” she says. Her father’s former boss gave him a break, and he landed a position as a construction supervisor. Employed illegally, he was paid minimum wage, far less than Iranians working the same job. “In Iran, the second time, it was really hard for me. I got the feeling that this wasn’t my country,” Mahnaz recalls. After 1979, following the Iranian Revolution, the country allowed children with proper refugee documentation to receive free education. “But still, some people weren’t happy. So the government brought lots of changes.” In 1997, the Iranian government introduced new sets of refugee laws that UNESCO says were designed to restrict the number of Afghan children in publicly funded schools. If a child wanted to attend school outside of the region where they received documentation as a refugee, they needed a travel permit. These permits had to be renewed four times a year, at a cost. In some cases, refugees could only register for schools in residential areas designated for Afghans. Unlike Iranian identification cards, those for Afghan refugees restricted them from traveling internationally, and buying a house or a car. The Right to Learn Without proper documentation, Mahnaz could not attend the Iranian school in her area. Instead, she had to pay additional school fees and attend a private Afghan school, which only taught children up until the fifth grade. To catch up on the years of school she missed when her family lived in Afghanistan, Mahnaz took classes during the summer as well. After completing elementary school, she applied again to enroll in an Iranian school. She was denied at first, but found a spot in the program’s night classes. During the school day, Mahnaz’s school officials harassed her and other Afghan students to pay tuition. “They were saying like, ‘you need to pay because you are Afghan.’ They would take out students during the class and like, kind of shame them in front of all the other students and telling them, ‘Oh you are Afghan, you need to come out and you need to pay.’ It was really hard.” Mahnaz’s family was struggling. Alone, her father worked to pay rent, support her sick mother and her five brothers and sisters, and pay their school tuition, all on a minimum wage. She feared she would have to stop going to school. Her school Principal knew she and her cousin were struggling, and found a way to pay their school fees. Mahnaz remembers what her Principal told her. “I know you are really hard-working people, and the way that our government is treating you is not right.” Life After the Taliban When it was time for Mahnaz to enter high school, she was told that she was no longer eligible to receive an education at Iranian schools. “Iran’s government came up with new policies every year. While Iranian kids could register early, Afghans had to wait for the Ministry of Education’s permission for months.” For the third time, her family felt they had no choice but to seek home elsewhere. Mahnaz’s brother and sister were still living in Afghanistan. Her brother, Rasoul, had a stable job with Catholic Relief Services, and he offered to support the family if they could manage to return. Facing growing discrimination, and with no possibility of further schooling for Mahnaz or her sisters, the Rezaies went back to Afghanistan in 2002. By that time, the United States had invaded Afghanistan and the Taliban had left Herat, scattering to other provinces. The community was still plagued by insecurity, so Rasoul encouraged Mahnaz to wear a burqa for protection. She had just started a job teaching English in a region where six years earlier, the Taliban stopped allowing education for girls. Rasoul’s mother-in-law insisted that Mahnaz and her sisters cover themselves, arguing, “they are beautiful, and people will kidnap them and kill them.” Rasoul got another job in Kabul, and the family moved. Mahnaz eventually found another job teaching English. In the years to come, she would work for the International Medical Corps, the Louis Berger Group, an American civil engineering company, and International Relief & Development. An American Life In 2007, Mahnaz came to the United States for the first time with an educational exchange program through the American Councils in Kabul. She and another young woman from Afghanistan stayed with a family in Knoxville, Iowa. At a party with the host family, a guest took out her cell phone and asked Mahnaz if she knew what it was. Mahnaz replied, “yeah, I know, because I have the same one in my purse.” “I got to eliminate some of my stereotypes about America — I didn’t know what America was — and then those students and people that I met in Iowa, after they got to know me and I told them my story, they got to see me and understand some of their own stereotypes, and how they were wrong about some of the things that they thought.” An American School When she returned to Afghanistan, she continued working in Kabul as a document control specialist for International Relief & Development, while starting her degree at the American University in Kabul. Her goal was to pursue a bachelor’s degree in the United States. A peer suggested that Mahnaz enroll in an online writing class for Afghan students hosted by Professor Hector Vila at Middlebury College in Vermont. Eventually, Vila encouraged her to apply to Middlebury, and she received a full four-year scholarship. Attending an American university challenged her. Growing up, she was used to what she describes as the “conservative environments” of Iran and Afghanistan. “I was very conscious not to make eye contact and other things. During the time I was in Kabul, I was wearing a long black veil. So when I came to the United States, I was wearing like, long coats and scarves, and I wasn’t shaking hands. It seems that when I was in my own culture, everything was—I kind of believed in that culture. And many things became invisible for me. I wasn’t seeing them. But when I traveled to the United States I saw much of the discrimination that women face in Afghanistan, but we don’t notice, we don’t recognize it. We think it’s natural.” Water for Herat After her freshman year, Mahnaz received a $10,000 grant through the college’s Davis Projects for Peace. Her project would bring clean water to people in a village in her home province of Herat. Her father helped her to build five hand-pumped wells, which they installed in four mosques and on a piece of privately donated land. After Mahnaz completed the project and returned to Middlebury, she received news that the Taliban had kidnapped the man who donated land for one of the wells. According to people in the villages where the wells were installed, the Taliban came asking about Mahnaz, “the girl who came from America and brought money.” Her father received a letter threatening them, her brothers, and herself. “When they sent the letter to my house they said, ‘we know that your boys are working with American NGOs, working with infidels. We know that your girls are in America, they came here.’ After that, everything got worse in Afghanistan for my family.” Her father moved the family again from Herat, to Kabul. And she started her application for asylum in the United States. “I got my green card two or three weeks ago.” Finding a Safe Haven For Mahnaz, the asylum process was easy. “Everybody says that I’m very lucky.” Three months after she filed her case, she was called for an interview. A week later, she was approved for asylum status. A week after that, she received a work permit. She waited a year to apply for her green card, and received it two months after that. Her sister, who applied for asylum at the same time, has been waiting two years for her initial interview. A friend who applied before them is still waiting. The New Immigrants Mahnaz is now in her second year of study at George Washington University’s Corcoran School of the Arts and Design. She’s pursuing a Master’s degree in New Media Photojournalism. She lives in Virginia with her husband. For her thesis, she’s making a documentary on Afghan immigrants. The project profiles people who entered the United States through the State Department’s Special Immigrant Visa (SIV) Program, which allows special issuance of visas to Afghan nationals who were employed by, or on behalf of the U.S. government in Afghanistan, or who served U.S. military personnel in NATO’s International Security Assistance Force. “Their lives are in danger in Afghanistan. And when they come here, they are given minimal benefits.” Mahnaz says the biggest challenge facing Afghans on SIVs is that they receive no help finding a job. “So they are struggling. But they come here, they don’t know the system, they don’t know how to find their way, they don’t know how to take transportation. Everything is new to them. Suddenly they face a culture where everything is new to them. Even like, crossing the streets. I can’t imagine, if legal immigrants face this many problems, how many problems face illegal immigrants? The people who come here, the majority, especially people who come from war zones, countries like Afghanistan or Syria, they come from very dangerous situations. From very unsafe situations. And they come to this country so they can have a future. And when you hear politicians, like Donald Trump says ‘Oh, they can’t come. We need to send them back,’ or these things, it’s very disappointing. Because he doesn’t understand. He hasn’t walked in the shoes of an immigrant. He hasn’t lost his child in the sea in Turkey. So he doesn’t understand. He lived a luxury life. So he doesn’t understand what immigrants go through.” Supporting Afghan Voices Mahnaz is also a poet. Since 2010, she’s been a mentor and English teacher for female students who are part of the Afghan Women’s Writing Project (AWWP), an online magazine featuring writing by Afghan women. Masha Hamilton, a journalist, author and literacy advocate, started the Project in 2009. The students participate in online writing workshops, giving them tools that empower them to find their voices and share their experiences of life in Afghanistan. The students submit their pieces online, and Mahnaz edits them and gives feedback. She also produces original poems and personal narratives for the AWWP website. “I write about my time in Afghanistan, living during the Taliban.” You can find her work at www.awwproject.org.The views presented in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of any other organization.