With each advancing year, more novel information technology is brought online, simultaneously advancing societal capabilities and dependence on new and legacy systems in areas as diverse as healthcare, finance, entertainment, defense, and critical infrastructure. Despite unceasing news of cyber attacks and various exploits that appear to strike into the nervous system of modern society, many information technology companies continue their long pattern of outsourcing risk, since—it is thought—building technology with security first in mind may make it harder to bring to market or less profitable.

Yet it is not only new information technology that is laden with obscure troubles. By now it should be apparent to anyone reading the news that legacy computer systems on which we all depend have fundamental weaknesses. Consider, for example, the “Heartbleed” and “Shellshock” vulnerabilities that just recently came to light, both of which exposed decades old problems that could still have very serious results on critical networks.

Today there is a constant dynamic at play of researchers finding holes and acting to plug them or criminals exploiting them first in so-called zero-day attacks. To put this in cybersecurity terms, the attack surface of our information-technology dominated society is vastly expanding and the gains in security are too few to cover us.

At the legal level, laws across the globe simply are not set to deal with today’s rapid technological change. Law is often reactive. At the commercial level there are clear reasons for not wanting to publicly discuss risk: admitting to risk may be akin to accepting legal responsibility and shareholders and customers may not be keen on your wares. At the national level, even for those countries that are updating their laws, the best that could be said is that they are in a state of flux and playing catch-up. In the U.S. we are using laws written in the 1980s to deal with novel and massive crimes, throwing the book at hacktivists and cybercriminals alike in one broad stroke. Internationally, it is worse, as countries hide behind difficulties in attribution, or do not have the capacity or desire to police their own people. So criminality continues essentially unabated and security flaws continue to crop up, while many outdated or inadequate laws are applied.

In terms of the rapid technological shifts all of us have seen, one might reasonably wonder how so many new security risks could be allowed to proliferate. The unsatisfying answer is that in many cases the original design was never built with security in mind. Consider that the internet, as Alexander Green put it “was originally intended for a few thousand researchers, not billions of users who don’t know or trust each other. So, the designers placed a higher premium on ease of use and decentralization over privacy and security.” The designers simply did not foresee that the internet would ultimately be used for commercial and military purposes, or become a haven for criminality.

Even though security concerns are a higher priority for companies now, there is a perpetual tradeoff between gaining users, dollars, and data, and locking down the technology and user data. Unsettling news such as celebrity or corporate hacks may temporarily increase vigilance in some cases, but there also appears to be a sense that security is becoming a hopeless cause. Even Bruce Schneier, among the most noted computer security experts, has said “Security is out of your control.” For certain, private corporations and the public continue to regularly compound problems by allowing and making considerable security tradeoffs for convenience.

At a macro-perspective, what we are currently seeing amassed against modern, IT-dependent society is an admixture of hacking, terrorism, espionage, and cyberwar. Consider these data points:

- • In 2011, the Kroll annual Global Fraud reported that the preceding year marked a milestone as it was the first time ever that the cost of electronic theft topped that of physical theft.

- • In Snowden’s wake, there has been a renewed focus on the efforts of intelligence agencies in cyberspace. Under that cover, many countries are thought to be exploiting loopholes and taking advantage of grey areas for industrial espionage while claiming that the U.S. does the same.

- • North Korea, Iran, China, and Russia are among countries that have cyber military units that many experts suspect are moving offensive disruption and destruction.

- • Politically oriented hacking groups like Lulzsec and Anonymous continue to operate, despite significant law enforcement activities against them.

- • Criminals are more prolific than ever, getting away with bigger heists, some of long duration—as in the Target and JPMorgan cases.

With cybersecurity measures being essentially tacked onto now critical infrastructure, it is no wonder that the idea of a new, more secure, attribution-enabled internet keeps cropping up. In February 2010, former NSA Director Mike McConnell wrote, “we need to reengineer the internet to make attribution, geolocation, intelligence analysis, and impact assessment—who did it, from where, why, and what was the result—more manageable.” A National Academy of Sciences report concluded that the attribution challenges are not primarily technical or engineering concerns: “[T]he most important barrier to deterrence today is not poor technical tools for attribution but issues that arise due to cross-jurisdictional attacks, especially multi-stage attacks. In other words, deterrence must be achieved through the governmental tools of state, and not by engineering design.”

Figure 1: Your daddy’s internet in the 70s

Figure 2: What the internet looked like by 2005

Marching Ahead to the Internet of Things

Into this unstable and dynamic mix comes the Internet of Things (or IoT for short). The IoT refers to uniquely identifiable physical objects and virtual representations in a network. Sometimes the IoT is described as a “thingaverse.” Importantly it is not people talking to people or people talking to things, but things communicating with things. (Some argue that people—through their always-on and ubiquitous smart devices—are among the first real mobile nodes for the IoT, as their devices constantly update other devices about location, speed, etc.)

At a conceptual level, the IoT is networked, automated, machine-to-machine awareness for processes such as data collection, remote monitoring, decision-making and taking.

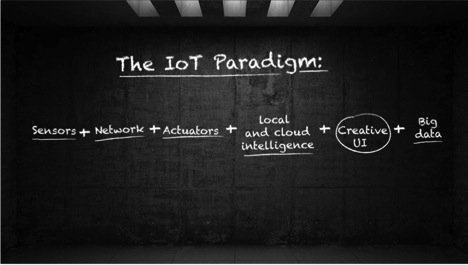

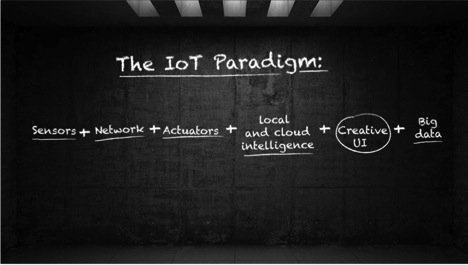

Figure 3: The IoT Paradigm

The IoT is not a new concept, but rather one with a relatively long history in information technology circles that is now being enabled by numerous advances. As with many technological and scientific innovations, there are several people who can rightly claim to have a stake in its creation. Individually in 1999 Bill Joy of Sun and Kevin Ashton of the Auto-ID Center at MIT proposed ideas that would become the Internet of Things, though the phrase itself is attributed to the Kevin Ashton.

At the domestic end of the spectrum the IoT initially was a solution looking for a problem–people had been looking to figure out how best to run their households with computers since the advent of the home computer industry. Today the Internet of Things is a term that encompasses many new internet-connected everyday objects in daily life, including household objects, even our cars, and many more industrial-scale processes. Another, more generic term of art Machine-to-Machine (M2M) is sometimes also used interchangeably.

How Will the IoT Work?

Broadly, it is thought that the Internet of Things will make things smarter by connecting devices and improving processes. This will be brought about through a variation on Metcalf’s Law that states that the “value of a telecommunications network is proportional to the square of the number of connected users of the system.” Likewise with the IoT the idea is that increased connectedness will also result in increased value and usefulness.

What Factors are Enabling the IoT?

Technological convergence and force multipliers are all coming into play: short-range communications technologies such as RFID, NFC, Bluetooth, and WiFi, plus recording devices, awareness algorithms, cloud storage and computing, big data, and analytics all are being brought to bear to create the IoT. Additionally, according to a recent McKinsey study there has been 80 to 90 percent reduction in prices for microelectromechanical systems (MEMS) and sensors over the past five years. MEMS are crucial for the IoT to have the ability to collect and act on data.

The IoT also depends on unique object IDs and so would be dashed without a new Internet Protocol (IP) to deal with the problem of internet address exhaustion. Internet Protocol version 6 (IPv6)—the latest revision of the communications protocol that provides an address system for computers on networks and routes traffic across the Internet—was developed by the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF). Given IPv6′s address space size it will be effectively impossible for it to ever reach its limitations. So, the IoT has unique addresses covered.

Big Data and Cloud Computing is a significant enabling factor. The 2014 EMC/IDC Digital Universe Report estimated that 40 percent of all data will be machine generated by 2020; it was 11 percent in 2005. Most of that data is in private hands and the drive to allow machines to make decisions is well along. As Nick Jones, research vice president and analyst at Gartner once said: “Computers can make sophisticated decisions based on data and knowledge, and they can communicate those decisions in our native language. To succeed at the pace of a digital world, you'll have to allow them to do so.”

Big Numbers

The time-honored investigative route of following the money indicates that some of this change is due to a push for new revenue streams. The desktop computing market is not as lucrative as it once was and mobile computing may become saturated; so M2M appears to be the next logical step for chip and device manufacturers and communication companies. Furthermore the potential money to be made from IoT awareness is apt to make today’s advertising dollars look small. When machines will be able to tell what is being used or when something is low on supplies, they will also be reporting data on human activities, the lifeblood of marketing firms.

In less than a decade estimates of the economic value of M2M and the IoT have moved from billion to trillions of dollars. In 2004, BusinessWeek predicted that M2M would be a $180 billion market by 2008. Two recent estimates may help induce perspective: General Electric estimates that the IoT will add $15 trillion to global GDP over next 20 years. McKinsey’s Global Institute May 2013 report suggests an economic impact of $2.7 trillion to $6.2 trillion annually by 2025—mainly in health care, infrastructure, and public sector services.

Intel plans to increase its research and development budget in the Internet of Things by 20 percent this year. It is clear that Intel's efforts are already paying off as it is breaking out its Internet of Things group into a separate operating segment. For Intel, the Internet of Things generated $482 million in revenue in the last quarter, which represented 32 percent growth year over year.

Already McKinsey is reporting an increase of 300 percent over the past five years in machine-to-machine devices. Likewise, CISCO recently estimated that 50 billion to 1 trillion things will be connected to the IoT across industries such as manufacturing, healthcare, and mining in ten years.

Security Concerns Proliferate

So, the current Internet of People is massively troubled by security concerns. We know that objects under computer control or accessible via the internet can be hacked, and that those hacks expose new risks. Hackers, whatever their motivation, can get into corporations and governments, households, cars, and small businesses, in effect anything “smart” and connected is a target. On the IoT’s home front, we have already seen hackers accessing poorly secured baby cameras, refrigerators, and thermostats. Given these realities, targeted digital hijacking is apt to be a growth business for criminals.

Greater risks will be seen in some areas as more devices are connected to the internet, especially critical infrastructures and services. With some 90 percent of critical infrastructure in the United States under private control, there are already serious vulnerabilities to contend with. Hacking will increase, as there will be more interesting targets everywhere and the ability to monetize hacks is apt to remain the same. The more things we see connected in this space, the more likely the sheer concentration of value will attract cyberterrorists, too.

Whether or not terrorists strike out in cyberspace, the IoT will have ugly failures that play out in the real world. To make matters worse, when real things go bad, retry and restart functions may be difficult or perhaps even impossible to implement. By comparison, the Flash Crash of 2010 that affected stock markets could be corrected, but how about when the impact is on actual things in the physical universe? And what would a “reset” button actually do?

In 2007 I noted that while cyber-terrorism of the sort that causes major damage or death through computer attacks has apparently not yet materialized, terrorists had clearly taken advantage of the strengths of the internet and web to gather intelligence, communicate, plan, recruit, fundraise, and—as in the case of beheading videos—frighten. And whereas just a few short years ago it seemed that terrorists would remain unlikely to engage in cyber attacks—due in part to the complexity involved in creating software—times have changed. The IoT touches real objects in the physical world, and as such will proliferate attractive targets for cyberterrorism. The IoT will have to contend with these problems.

Seven Unintended Consequences of the IoT

- 1. Loss of privacy: Already to some this is a lost cause. However, the IoT is apt to be a force multiplier as connected devices can transmit data back to companies. What does that mean for privacy? How should privacy risks be weighed against potential societal benefits, such as the ability to generate better data to improve health-care decision-making or to promote energy efficiency?

- 2. Unforeseen and unequal distribution: Amplifying the digital divide. As William Gibson once said, "The future is here, it’s just unevenly distributed." So too with the IoT, as developed nations and well-off locales are apt to first experience the benefits (and potential downsides). Will the IoT really benefit all or just increase disparities?

- 3. Pre-crime forecasting: Something that Philip K. Dick dreamt up may become real as machines report on the digital exhaust of devices that humans use or that their devices come into contact with.

- 4. Unforeseen spill-over effects: An accident or attack may now result in a wide-ranging power blackout, for example. This is likely to happen with greater frequency as more devices are brought online.

- 5. Economics disrupted as certain skills become less important, we “teach the machine”: Jobs are apt to be lost. For example, with automated transport, truck and bus drivers and other paid drivers may be among the first to lose their jobs. Already, the mining company Rio Tinto is employing driverless trucks for transporting ore.

- 6. Loss of ability to maintain understanding and control: the systems we make may become more complex together than we can imagine and control. Increased complexity is apt to come with unforeseen costs.

- 7. Merging the virtual with the physical, making for many new, attractive targets: From targeted cyber hacks to cyberterrorism, the IoT’s proliferation of new devices is apt to be awfully tempting to national, amateur, and for-hire hackers.

The Role of Government

Clearly, the modern IT-dependent society needs a massive thinking upgrade to help understand risk, plan for the future, and keep harm to a minimum while continuing to enjoy the remarkable benefits of information technologies. When corporations are reckless with security, it is often not till much later that society finds out about the risks that were run. As William Jackson of Government Computer News noted “industry and private sector companies have a vested interest in maintaining adequate security and that regulation should be kept at a minimum. But companies have always had that interest, and to date it has not translated into adequate security.” Government is not blameless either, as the tasks of keeping up with technological change and risk are squarely on thinly stretched forces; however, too often there has been a willingness to accept corporate decisions and leadership in lieu of government oversight. What we are left with is the knowledge that government and industry must redouble their efforts to understand risks, improve services, and monitor technologies, and that in particular with the IoT, standards and controls must be well understood to limit unintended consequences. Pursuing such an agenda would best be achieved by working internationally with other governments and with multinational corporations and NGOs, as each have a stake. Dealing with these persistent, international threats and novel risks means having to cooperatively create and enforce standards, advance new laws, and pursue negligence and criminality.

Our current computing technology predicament is a far cry from Mark Weiser and John Seely Brown’s concept of “Calm Technology” that they penned in 1995: “that which informs but doesn't demand our focus or attention.” However, the concept may be an excellent way to plan for the IoT world with these principles in mind:

- The purpose of a computer is to help you do something else.

- The best computer is a quiet, invisible servant.

- The more you can do by intuition the smarter you are; the computer should extend your unconscious.

- Technology should create calm.

Executing on such a plan would require government leadership and willingness to change and compromise across the board. While this might seem a tall order for government, the alternative appears to be tacitly accepting worsening security for all. Enlightened government has a responsibility to help create calm.

Sean S. Costigan is a consultant, educator and Senior Adviser to the Emerging Security Challenges Working Group of the Partnership for Peace Consortium. The views expressed here are solely his own.

This article was originally published in the Diplomatic Courier's November/December 2014 print edition.

a global affairs media network

Cybersecurity, the Internet of Things, and the Role of Government

December 2, 2014

With each advancing year, more novel information technology is brought online, simultaneously advancing societal capabilities and dependence on new and legacy systems in areas as diverse as healthcare, finance, entertainment, defense, and critical infrastructure. Despite unceasing news of cyber attacks and various exploits that appear to strike into the nervous system of modern society, many information technology companies continue their long pattern of outsourcing risk, since—it is thought—building technology with security first in mind may make it harder to bring to market or less profitable.

Yet it is not only new information technology that is laden with obscure troubles. By now it should be apparent to anyone reading the news that legacy computer systems on which we all depend have fundamental weaknesses. Consider, for example, the “Heartbleed” and “Shellshock” vulnerabilities that just recently came to light, both of which exposed decades old problems that could still have very serious results on critical networks.

Today there is a constant dynamic at play of researchers finding holes and acting to plug them or criminals exploiting them first in so-called zero-day attacks. To put this in cybersecurity terms, the attack surface of our information-technology dominated society is vastly expanding and the gains in security are too few to cover us.

At the legal level, laws across the globe simply are not set to deal with today’s rapid technological change. Law is often reactive. At the commercial level there are clear reasons for not wanting to publicly discuss risk: admitting to risk may be akin to accepting legal responsibility and shareholders and customers may not be keen on your wares. At the national level, even for those countries that are updating their laws, the best that could be said is that they are in a state of flux and playing catch-up. In the U.S. we are using laws written in the 1980s to deal with novel and massive crimes, throwing the book at hacktivists and cybercriminals alike in one broad stroke. Internationally, it is worse, as countries hide behind difficulties in attribution, or do not have the capacity or desire to police their own people. So criminality continues essentially unabated and security flaws continue to crop up, while many outdated or inadequate laws are applied.

In terms of the rapid technological shifts all of us have seen, one might reasonably wonder how so many new security risks could be allowed to proliferate. The unsatisfying answer is that in many cases the original design was never built with security in mind. Consider that the internet, as Alexander Green put it “was originally intended for a few thousand researchers, not billions of users who don’t know or trust each other. So, the designers placed a higher premium on ease of use and decentralization over privacy and security.” The designers simply did not foresee that the internet would ultimately be used for commercial and military purposes, or become a haven for criminality.

Even though security concerns are a higher priority for companies now, there is a perpetual tradeoff between gaining users, dollars, and data, and locking down the technology and user data. Unsettling news such as celebrity or corporate hacks may temporarily increase vigilance in some cases, but there also appears to be a sense that security is becoming a hopeless cause. Even Bruce Schneier, among the most noted computer security experts, has said “Security is out of your control.” For certain, private corporations and the public continue to regularly compound problems by allowing and making considerable security tradeoffs for convenience.

At a macro-perspective, what we are currently seeing amassed against modern, IT-dependent society is an admixture of hacking, terrorism, espionage, and cyberwar. Consider these data points:

- • In 2011, the Kroll annual Global Fraud reported that the preceding year marked a milestone as it was the first time ever that the cost of electronic theft topped that of physical theft.

- • In Snowden’s wake, there has been a renewed focus on the efforts of intelligence agencies in cyberspace. Under that cover, many countries are thought to be exploiting loopholes and taking advantage of grey areas for industrial espionage while claiming that the U.S. does the same.

- • North Korea, Iran, China, and Russia are among countries that have cyber military units that many experts suspect are moving offensive disruption and destruction.

- • Politically oriented hacking groups like Lulzsec and Anonymous continue to operate, despite significant law enforcement activities against them.

- • Criminals are more prolific than ever, getting away with bigger heists, some of long duration—as in the Target and JPMorgan cases.

With cybersecurity measures being essentially tacked onto now critical infrastructure, it is no wonder that the idea of a new, more secure, attribution-enabled internet keeps cropping up. In February 2010, former NSA Director Mike McConnell wrote, “we need to reengineer the internet to make attribution, geolocation, intelligence analysis, and impact assessment—who did it, from where, why, and what was the result—more manageable.” A National Academy of Sciences report concluded that the attribution challenges are not primarily technical or engineering concerns: “[T]he most important barrier to deterrence today is not poor technical tools for attribution but issues that arise due to cross-jurisdictional attacks, especially multi-stage attacks. In other words, deterrence must be achieved through the governmental tools of state, and not by engineering design.”

Figure 1: Your daddy’s internet in the 70s

Figure 2: What the internet looked like by 2005

Marching Ahead to the Internet of Things

Into this unstable and dynamic mix comes the Internet of Things (or IoT for short). The IoT refers to uniquely identifiable physical objects and virtual representations in a network. Sometimes the IoT is described as a “thingaverse.” Importantly it is not people talking to people or people talking to things, but things communicating with things. (Some argue that people—through their always-on and ubiquitous smart devices—are among the first real mobile nodes for the IoT, as their devices constantly update other devices about location, speed, etc.)

At a conceptual level, the IoT is networked, automated, machine-to-machine awareness for processes such as data collection, remote monitoring, decision-making and taking.

Figure 3: The IoT Paradigm

The IoT is not a new concept, but rather one with a relatively long history in information technology circles that is now being enabled by numerous advances. As with many technological and scientific innovations, there are several people who can rightly claim to have a stake in its creation. Individually in 1999 Bill Joy of Sun and Kevin Ashton of the Auto-ID Center at MIT proposed ideas that would become the Internet of Things, though the phrase itself is attributed to the Kevin Ashton.

At the domestic end of the spectrum the IoT initially was a solution looking for a problem–people had been looking to figure out how best to run their households with computers since the advent of the home computer industry. Today the Internet of Things is a term that encompasses many new internet-connected everyday objects in daily life, including household objects, even our cars, and many more industrial-scale processes. Another, more generic term of art Machine-to-Machine (M2M) is sometimes also used interchangeably.

How Will the IoT Work?

Broadly, it is thought that the Internet of Things will make things smarter by connecting devices and improving processes. This will be brought about through a variation on Metcalf’s Law that states that the “value of a telecommunications network is proportional to the square of the number of connected users of the system.” Likewise with the IoT the idea is that increased connectedness will also result in increased value and usefulness.

What Factors are Enabling the IoT?

Technological convergence and force multipliers are all coming into play: short-range communications technologies such as RFID, NFC, Bluetooth, and WiFi, plus recording devices, awareness algorithms, cloud storage and computing, big data, and analytics all are being brought to bear to create the IoT. Additionally, according to a recent McKinsey study there has been 80 to 90 percent reduction in prices for microelectromechanical systems (MEMS) and sensors over the past five years. MEMS are crucial for the IoT to have the ability to collect and act on data.

The IoT also depends on unique object IDs and so would be dashed without a new Internet Protocol (IP) to deal with the problem of internet address exhaustion. Internet Protocol version 6 (IPv6)—the latest revision of the communications protocol that provides an address system for computers on networks and routes traffic across the Internet—was developed by the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF). Given IPv6′s address space size it will be effectively impossible for it to ever reach its limitations. So, the IoT has unique addresses covered.

Big Data and Cloud Computing is a significant enabling factor. The 2014 EMC/IDC Digital Universe Report estimated that 40 percent of all data will be machine generated by 2020; it was 11 percent in 2005. Most of that data is in private hands and the drive to allow machines to make decisions is well along. As Nick Jones, research vice president and analyst at Gartner once said: “Computers can make sophisticated decisions based on data and knowledge, and they can communicate those decisions in our native language. To succeed at the pace of a digital world, you'll have to allow them to do so.”

Big Numbers

The time-honored investigative route of following the money indicates that some of this change is due to a push for new revenue streams. The desktop computing market is not as lucrative as it once was and mobile computing may become saturated; so M2M appears to be the next logical step for chip and device manufacturers and communication companies. Furthermore the potential money to be made from IoT awareness is apt to make today’s advertising dollars look small. When machines will be able to tell what is being used or when something is low on supplies, they will also be reporting data on human activities, the lifeblood of marketing firms.

In less than a decade estimates of the economic value of M2M and the IoT have moved from billion to trillions of dollars. In 2004, BusinessWeek predicted that M2M would be a $180 billion market by 2008. Two recent estimates may help induce perspective: General Electric estimates that the IoT will add $15 trillion to global GDP over next 20 years. McKinsey’s Global Institute May 2013 report suggests an economic impact of $2.7 trillion to $6.2 trillion annually by 2025—mainly in health care, infrastructure, and public sector services.

Intel plans to increase its research and development budget in the Internet of Things by 20 percent this year. It is clear that Intel's efforts are already paying off as it is breaking out its Internet of Things group into a separate operating segment. For Intel, the Internet of Things generated $482 million in revenue in the last quarter, which represented 32 percent growth year over year.

Already McKinsey is reporting an increase of 300 percent over the past five years in machine-to-machine devices. Likewise, CISCO recently estimated that 50 billion to 1 trillion things will be connected to the IoT across industries such as manufacturing, healthcare, and mining in ten years.

Security Concerns Proliferate

So, the current Internet of People is massively troubled by security concerns. We know that objects under computer control or accessible via the internet can be hacked, and that those hacks expose new risks. Hackers, whatever their motivation, can get into corporations and governments, households, cars, and small businesses, in effect anything “smart” and connected is a target. On the IoT’s home front, we have already seen hackers accessing poorly secured baby cameras, refrigerators, and thermostats. Given these realities, targeted digital hijacking is apt to be a growth business for criminals.

Greater risks will be seen in some areas as more devices are connected to the internet, especially critical infrastructures and services. With some 90 percent of critical infrastructure in the United States under private control, there are already serious vulnerabilities to contend with. Hacking will increase, as there will be more interesting targets everywhere and the ability to monetize hacks is apt to remain the same. The more things we see connected in this space, the more likely the sheer concentration of value will attract cyberterrorists, too.

Whether or not terrorists strike out in cyberspace, the IoT will have ugly failures that play out in the real world. To make matters worse, when real things go bad, retry and restart functions may be difficult or perhaps even impossible to implement. By comparison, the Flash Crash of 2010 that affected stock markets could be corrected, but how about when the impact is on actual things in the physical universe? And what would a “reset” button actually do?

In 2007 I noted that while cyber-terrorism of the sort that causes major damage or death through computer attacks has apparently not yet materialized, terrorists had clearly taken advantage of the strengths of the internet and web to gather intelligence, communicate, plan, recruit, fundraise, and—as in the case of beheading videos—frighten. And whereas just a few short years ago it seemed that terrorists would remain unlikely to engage in cyber attacks—due in part to the complexity involved in creating software—times have changed. The IoT touches real objects in the physical world, and as such will proliferate attractive targets for cyberterrorism. The IoT will have to contend with these problems.

Seven Unintended Consequences of the IoT

- 1. Loss of privacy: Already to some this is a lost cause. However, the IoT is apt to be a force multiplier as connected devices can transmit data back to companies. What does that mean for privacy? How should privacy risks be weighed against potential societal benefits, such as the ability to generate better data to improve health-care decision-making or to promote energy efficiency?

- 2. Unforeseen and unequal distribution: Amplifying the digital divide. As William Gibson once said, "The future is here, it’s just unevenly distributed." So too with the IoT, as developed nations and well-off locales are apt to first experience the benefits (and potential downsides). Will the IoT really benefit all or just increase disparities?

- 3. Pre-crime forecasting: Something that Philip K. Dick dreamt up may become real as machines report on the digital exhaust of devices that humans use or that their devices come into contact with.

- 4. Unforeseen spill-over effects: An accident or attack may now result in a wide-ranging power blackout, for example. This is likely to happen with greater frequency as more devices are brought online.

- 5. Economics disrupted as certain skills become less important, we “teach the machine”: Jobs are apt to be lost. For example, with automated transport, truck and bus drivers and other paid drivers may be among the first to lose their jobs. Already, the mining company Rio Tinto is employing driverless trucks for transporting ore.

- 6. Loss of ability to maintain understanding and control: the systems we make may become more complex together than we can imagine and control. Increased complexity is apt to come with unforeseen costs.

- 7. Merging the virtual with the physical, making for many new, attractive targets: From targeted cyber hacks to cyberterrorism, the IoT’s proliferation of new devices is apt to be awfully tempting to national, amateur, and for-hire hackers.

The Role of Government

Clearly, the modern IT-dependent society needs a massive thinking upgrade to help understand risk, plan for the future, and keep harm to a minimum while continuing to enjoy the remarkable benefits of information technologies. When corporations are reckless with security, it is often not till much later that society finds out about the risks that were run. As William Jackson of Government Computer News noted “industry and private sector companies have a vested interest in maintaining adequate security and that regulation should be kept at a minimum. But companies have always had that interest, and to date it has not translated into adequate security.” Government is not blameless either, as the tasks of keeping up with technological change and risk are squarely on thinly stretched forces; however, too often there has been a willingness to accept corporate decisions and leadership in lieu of government oversight. What we are left with is the knowledge that government and industry must redouble their efforts to understand risks, improve services, and monitor technologies, and that in particular with the IoT, standards and controls must be well understood to limit unintended consequences. Pursuing such an agenda would best be achieved by working internationally with other governments and with multinational corporations and NGOs, as each have a stake. Dealing with these persistent, international threats and novel risks means having to cooperatively create and enforce standards, advance new laws, and pursue negligence and criminality.

Our current computing technology predicament is a far cry from Mark Weiser and John Seely Brown’s concept of “Calm Technology” that they penned in 1995: “that which informs but doesn't demand our focus or attention.” However, the concept may be an excellent way to plan for the IoT world with these principles in mind:

- The purpose of a computer is to help you do something else.

- The best computer is a quiet, invisible servant.

- The more you can do by intuition the smarter you are; the computer should extend your unconscious.

- Technology should create calm.

Executing on such a plan would require government leadership and willingness to change and compromise across the board. While this might seem a tall order for government, the alternative appears to be tacitly accepting worsening security for all. Enlightened government has a responsibility to help create calm.

Sean S. Costigan is a consultant, educator and Senior Adviser to the Emerging Security Challenges Working Group of the Partnership for Peace Consortium. The views expressed here are solely his own.

This article was originally published in the Diplomatic Courier's November/December 2014 print edition.