.

The COP 21 summit in Paris has generally been described a major breakthrough for climate negotiations, one that would presumably provide the long overdue impetus for developing a sustainable solution to the climate change crisis. However, after so many false starts, one cannot help wonder whether the outcome of the COP 21 climate summit does indeed qualify as a negotiation breakthrough, or perhaps our expectations are again too optimistic. In other words, how can we evaluate the outcome of COP 21 as being consistent with a negotiation breakthrough as opposed to a negotiation breakdown or to business as usual (neither breakthrough nor breakdown)? In an article I published in 2014 in the journal of International Negotiation, I drew on insights offered by market trading theory to introduce a framework of negotiation breakthrough analysis (NBA) that should allow us to address this important question.

My key departing point is that the outcome of each round of climate negotiations is path-dependently shaped by the results of previous meetings. In other words, decisions taken at previous COPs inform, shape and constrain parties’ expectations regarding the outcome of future COPs. The way in which parties then meet these expectations, or fail to do so, define the overall levels of support and resistance of the negotiations. As long as COP negotiation outcomes stay within the established levels of support and resistance, there is no breakthrough or breakdown, just business as usual. However, once the levels of expectations generated by previous outcomes are breached then negotiation breakthroughs are likely to occur. Positive breakthroughs take place when negotiations move outside the resistance level as they help push the negotiation agenda forward. Negative breakthroughs (or breakdowns) take place when the support level is pierced as they prompt parties to re-visit files already agreed upon.

My model proved accurate in explaining the evolution of climate negotiations from 1995 (COP1) to 2012 (COP18), when the empirical analysis was conducted. In an effort to test the validity of my conceptual framework against the outcome of the 2015 climate summit in Paris, I have collected new quantitative (COP decisions) and qualitative date (interviews with climate experts), re-calculated the support and resistance levels, and plotted the results in the graph shown in Fig 1. The analysis confirms, in rather unequivocal terms, that the public recognition of COP 21 as a negotiation breakthrough has not been misplaced. The resistance level shaped by the outcomes of previous COP negotiations has been forcefully breached, a fact that provides strong evidence about the climate agenda moving forward as opposed to getting stalled or addressing old issues. The graph also shows that the outcome of COP 21 is not the result of an abrupt or hasty move, but it has been steadily prepared by multiple rounds of negotiations taking place after the much criticised COP 15 meeting in Copenhagen.

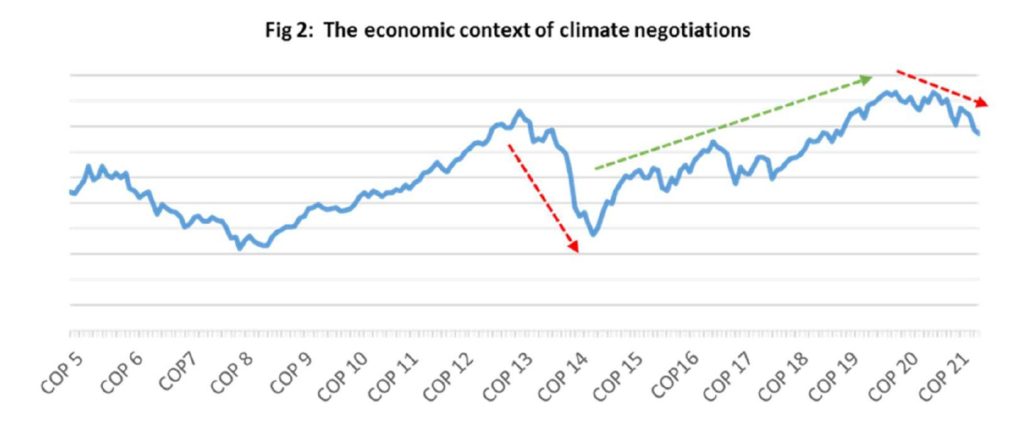

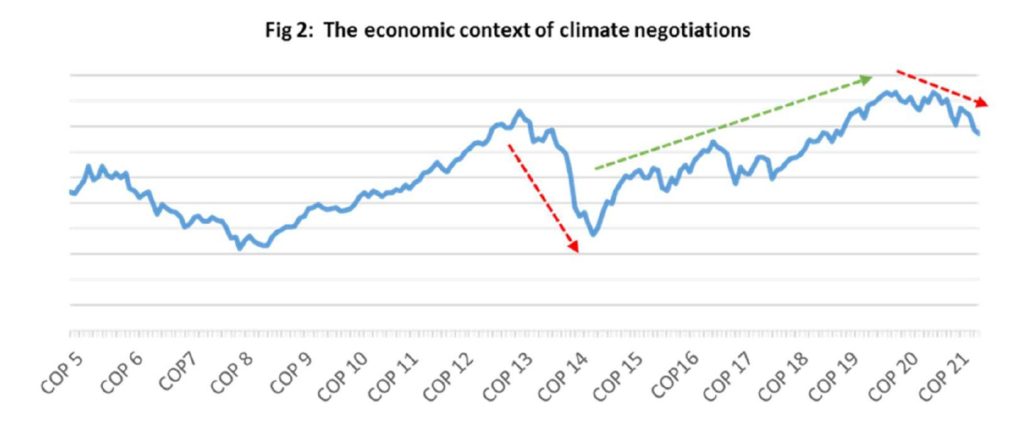

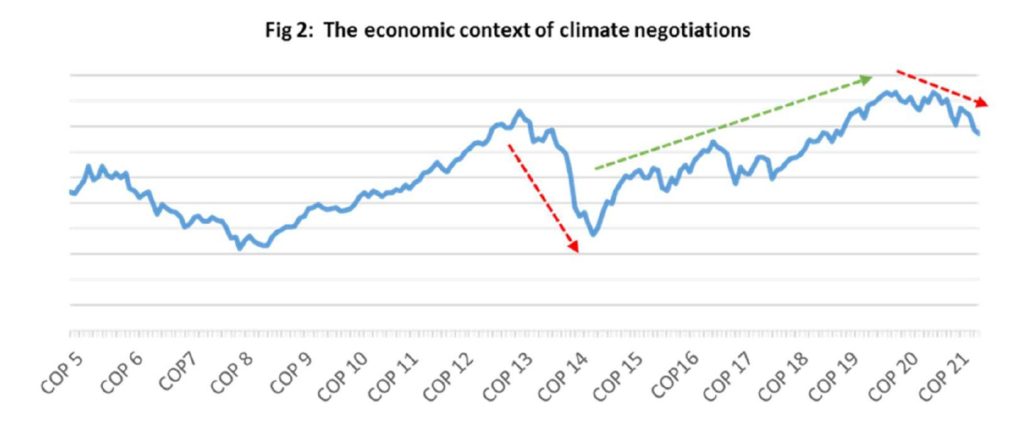

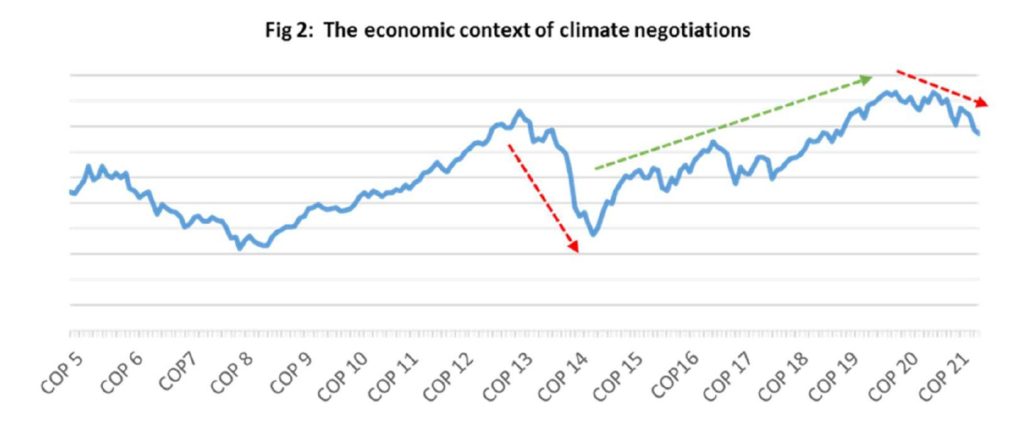

What Fig 1 is not able to tell us is whether the COP 21 breakthrough is sustainable that is, whether we should expect climate negotiations to continue on the current positive trend or they would likely reverse to a zig-zag or negative pattern. As I’ve argued elsewhere, the sustainability of a negotiation breakthrough cannot be predicted using data pertaining only to negotiation outcomes. The analysis must also take into account the broader economic context in which negotiations take place. In other words, the momentum of international negotiations is contingent upon them taking place in a favourable context, which in the case of climate change is largely informed by the evolution of the oil price and the influence of the sustainable economic sector. Higher oil prices tend to stimulate interest in renewable energy policies, while the expansion of sustainable industries increases the opportunity costs of reversing to carbon-intensive modes of production.

The index created by combining the oil spot price and the Dow Jones Sustainability World Index (DJSWI) is shown in Fig 2 and offers a rather sober view regarding the short term future of climate negotiations. The tremendous pressure of the global financial crisis in 2008-2009 broke the momentum of climate negotiations at COP 15 in Copenhagen (first red arrow). The economic context has steadily improved afterwards (green arrow), but it seems to enter a slight period of retraction (second red arrow), which might not bode well for the immediate future of climate negotiations.

What Fig 1 is not able to tell us is whether the COP 21 breakthrough is sustainable that is, whether we should expect climate negotiations to continue on the current positive trend or they would likely reverse to a zig-zag or negative pattern. As I’ve argued elsewhere, the sustainability of a negotiation breakthrough cannot be predicted using data pertaining only to negotiation outcomes. The analysis must also take into account the broader economic context in which negotiations take place. In other words, the momentum of international negotiations is contingent upon them taking place in a favourable context, which in the case of climate change is largely informed by the evolution of the oil price and the influence of the sustainable economic sector. Higher oil prices tend to stimulate interest in renewable energy policies, while the expansion of sustainable industries increases the opportunity costs of reversing to carbon-intensive modes of production.

The index created by combining the oil spot price and the Dow Jones Sustainability World Index (DJSWI) is shown in Fig 2 and offers a rather sober view regarding the short term future of climate negotiations. The tremendous pressure of the global financial crisis in 2008-2009 broke the momentum of climate negotiations at COP 15 in Copenhagen (first red arrow). The economic context has steadily improved afterwards (green arrow), but it seems to enter a slight period of retraction (second red arrow), which might not bode well for the immediate future of climate negotiations.

To conclude, COP 21 does qualify as a negotiation breakthrough because its outcome has substantially exceeded the parties’ expectations about what needs to be accomplished in order to address the climate change crisis. What is less clear is whether COP 22 in Marrakech in November 2016 will be able to build on COP21’s momentum and continue its positive agenda. The collapse of the oil price in the past year has introduced a negative pressure point in the broader context of the negotiations, which the sustainability economic sector might not be able to offset.

About the Author: Corneliu Bjola is Associate Professor in Diplomatic Studies at the University of Oxford. His research interests lie at the intersection of diplomatic studies, negotiation theory, international ethics, and crisis management. He has authored or edited five books, including the recent co-edited volumes on Secret Diplomacy: Concepts, Contexts and Cases (2016) and Digital Diplomacy: Theory and Practice (2015). His work has been published in the European Journal of International Relations, International Negotiation, Review of International Studies, British Journal of Politics and International Relations, Global Policy, Journal of Global Ethics and The Hague Journal of Diplomacy. Bjola is Co-Editor of the book series on “New Diplomatic Studies” with Routledge and Editor-in-Chief of the new journal “Diplomacy and Foreign Policy” with Brill.

To conclude, COP 21 does qualify as a negotiation breakthrough because its outcome has substantially exceeded the parties’ expectations about what needs to be accomplished in order to address the climate change crisis. What is less clear is whether COP 22 in Marrakech in November 2016 will be able to build on COP21’s momentum and continue its positive agenda. The collapse of the oil price in the past year has introduced a negative pressure point in the broader context of the negotiations, which the sustainability economic sector might not be able to offset.

About the Author: Corneliu Bjola is Associate Professor in Diplomatic Studies at the University of Oxford. His research interests lie at the intersection of diplomatic studies, negotiation theory, international ethics, and crisis management. He has authored or edited five books, including the recent co-edited volumes on Secret Diplomacy: Concepts, Contexts and Cases (2016) and Digital Diplomacy: Theory and Practice (2015). His work has been published in the European Journal of International Relations, International Negotiation, Review of International Studies, British Journal of Politics and International Relations, Global Policy, Journal of Global Ethics and The Hague Journal of Diplomacy. Bjola is Co-Editor of the book series on “New Diplomatic Studies” with Routledge and Editor-in-Chief of the new journal “Diplomacy and Foreign Policy” with Brill.

What Fig 1 is not able to tell us is whether the COP 21 breakthrough is sustainable that is, whether we should expect climate negotiations to continue on the current positive trend or they would likely reverse to a zig-zag or negative pattern. As I’ve argued elsewhere, the sustainability of a negotiation breakthrough cannot be predicted using data pertaining only to negotiation outcomes. The analysis must also take into account the broader economic context in which negotiations take place. In other words, the momentum of international negotiations is contingent upon them taking place in a favourable context, which in the case of climate change is largely informed by the evolution of the oil price and the influence of the sustainable economic sector. Higher oil prices tend to stimulate interest in renewable energy policies, while the expansion of sustainable industries increases the opportunity costs of reversing to carbon-intensive modes of production.

The index created by combining the oil spot price and the Dow Jones Sustainability World Index (DJSWI) is shown in Fig 2 and offers a rather sober view regarding the short term future of climate negotiations. The tremendous pressure of the global financial crisis in 2008-2009 broke the momentum of climate negotiations at COP 15 in Copenhagen (first red arrow). The economic context has steadily improved afterwards (green arrow), but it seems to enter a slight period of retraction (second red arrow), which might not bode well for the immediate future of climate negotiations.

What Fig 1 is not able to tell us is whether the COP 21 breakthrough is sustainable that is, whether we should expect climate negotiations to continue on the current positive trend or they would likely reverse to a zig-zag or negative pattern. As I’ve argued elsewhere, the sustainability of a negotiation breakthrough cannot be predicted using data pertaining only to negotiation outcomes. The analysis must also take into account the broader economic context in which negotiations take place. In other words, the momentum of international negotiations is contingent upon them taking place in a favourable context, which in the case of climate change is largely informed by the evolution of the oil price and the influence of the sustainable economic sector. Higher oil prices tend to stimulate interest in renewable energy policies, while the expansion of sustainable industries increases the opportunity costs of reversing to carbon-intensive modes of production.

The index created by combining the oil spot price and the Dow Jones Sustainability World Index (DJSWI) is shown in Fig 2 and offers a rather sober view regarding the short term future of climate negotiations. The tremendous pressure of the global financial crisis in 2008-2009 broke the momentum of climate negotiations at COP 15 in Copenhagen (first red arrow). The economic context has steadily improved afterwards (green arrow), but it seems to enter a slight period of retraction (second red arrow), which might not bode well for the immediate future of climate negotiations.

To conclude, COP 21 does qualify as a negotiation breakthrough because its outcome has substantially exceeded the parties’ expectations about what needs to be accomplished in order to address the climate change crisis. What is less clear is whether COP 22 in Marrakech in November 2016 will be able to build on COP21’s momentum and continue its positive agenda. The collapse of the oil price in the past year has introduced a negative pressure point in the broader context of the negotiations, which the sustainability economic sector might not be able to offset.

About the Author: Corneliu Bjola is Associate Professor in Diplomatic Studies at the University of Oxford. His research interests lie at the intersection of diplomatic studies, negotiation theory, international ethics, and crisis management. He has authored or edited five books, including the recent co-edited volumes on Secret Diplomacy: Concepts, Contexts and Cases (2016) and Digital Diplomacy: Theory and Practice (2015). His work has been published in the European Journal of International Relations, International Negotiation, Review of International Studies, British Journal of Politics and International Relations, Global Policy, Journal of Global Ethics and The Hague Journal of Diplomacy. Bjola is Co-Editor of the book series on “New Diplomatic Studies” with Routledge and Editor-in-Chief of the new journal “Diplomacy and Foreign Policy” with Brill.

To conclude, COP 21 does qualify as a negotiation breakthrough because its outcome has substantially exceeded the parties’ expectations about what needs to be accomplished in order to address the climate change crisis. What is less clear is whether COP 22 in Marrakech in November 2016 will be able to build on COP21’s momentum and continue its positive agenda. The collapse of the oil price in the past year has introduced a negative pressure point in the broader context of the negotiations, which the sustainability economic sector might not be able to offset.

About the Author: Corneliu Bjola is Associate Professor in Diplomatic Studies at the University of Oxford. His research interests lie at the intersection of diplomatic studies, negotiation theory, international ethics, and crisis management. He has authored or edited five books, including the recent co-edited volumes on Secret Diplomacy: Concepts, Contexts and Cases (2016) and Digital Diplomacy: Theory and Practice (2015). His work has been published in the European Journal of International Relations, International Negotiation, Review of International Studies, British Journal of Politics and International Relations, Global Policy, Journal of Global Ethics and The Hague Journal of Diplomacy. Bjola is Co-Editor of the book series on “New Diplomatic Studies” with Routledge and Editor-in-Chief of the new journal “Diplomacy and Foreign Policy” with Brill.

The views presented in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of any other organization.

a global affairs media network

The State of Climate Negotiations: What to Expect after COP 21?

||

June 9, 2016

The COP 21 summit in Paris has generally been described a major breakthrough for climate negotiations, one that would presumably provide the long overdue impetus for developing a sustainable solution to the climate change crisis. However, after so many false starts, one cannot help wonder whether the outcome of the COP 21 climate summit does indeed qualify as a negotiation breakthrough, or perhaps our expectations are again too optimistic. In other words, how can we evaluate the outcome of COP 21 as being consistent with a negotiation breakthrough as opposed to a negotiation breakdown or to business as usual (neither breakthrough nor breakdown)? In an article I published in 2014 in the journal of International Negotiation, I drew on insights offered by market trading theory to introduce a framework of negotiation breakthrough analysis (NBA) that should allow us to address this important question.

My key departing point is that the outcome of each round of climate negotiations is path-dependently shaped by the results of previous meetings. In other words, decisions taken at previous COPs inform, shape and constrain parties’ expectations regarding the outcome of future COPs. The way in which parties then meet these expectations, or fail to do so, define the overall levels of support and resistance of the negotiations. As long as COP negotiation outcomes stay within the established levels of support and resistance, there is no breakthrough or breakdown, just business as usual. However, once the levels of expectations generated by previous outcomes are breached then negotiation breakthroughs are likely to occur. Positive breakthroughs take place when negotiations move outside the resistance level as they help push the negotiation agenda forward. Negative breakthroughs (or breakdowns) take place when the support level is pierced as they prompt parties to re-visit files already agreed upon.

My model proved accurate in explaining the evolution of climate negotiations from 1995 (COP1) to 2012 (COP18), when the empirical analysis was conducted. In an effort to test the validity of my conceptual framework against the outcome of the 2015 climate summit in Paris, I have collected new quantitative (COP decisions) and qualitative date (interviews with climate experts), re-calculated the support and resistance levels, and plotted the results in the graph shown in Fig 1. The analysis confirms, in rather unequivocal terms, that the public recognition of COP 21 as a negotiation breakthrough has not been misplaced. The resistance level shaped by the outcomes of previous COP negotiations has been forcefully breached, a fact that provides strong evidence about the climate agenda moving forward as opposed to getting stalled or addressing old issues. The graph also shows that the outcome of COP 21 is not the result of an abrupt or hasty move, but it has been steadily prepared by multiple rounds of negotiations taking place after the much criticised COP 15 meeting in Copenhagen.

What Fig 1 is not able to tell us is whether the COP 21 breakthrough is sustainable that is, whether we should expect climate negotiations to continue on the current positive trend or they would likely reverse to a zig-zag or negative pattern. As I’ve argued elsewhere, the sustainability of a negotiation breakthrough cannot be predicted using data pertaining only to negotiation outcomes. The analysis must also take into account the broader economic context in which negotiations take place. In other words, the momentum of international negotiations is contingent upon them taking place in a favourable context, which in the case of climate change is largely informed by the evolution of the oil price and the influence of the sustainable economic sector. Higher oil prices tend to stimulate interest in renewable energy policies, while the expansion of sustainable industries increases the opportunity costs of reversing to carbon-intensive modes of production.

The index created by combining the oil spot price and the Dow Jones Sustainability World Index (DJSWI) is shown in Fig 2 and offers a rather sober view regarding the short term future of climate negotiations. The tremendous pressure of the global financial crisis in 2008-2009 broke the momentum of climate negotiations at COP 15 in Copenhagen (first red arrow). The economic context has steadily improved afterwards (green arrow), but it seems to enter a slight period of retraction (second red arrow), which might not bode well for the immediate future of climate negotiations.

What Fig 1 is not able to tell us is whether the COP 21 breakthrough is sustainable that is, whether we should expect climate negotiations to continue on the current positive trend or they would likely reverse to a zig-zag or negative pattern. As I’ve argued elsewhere, the sustainability of a negotiation breakthrough cannot be predicted using data pertaining only to negotiation outcomes. The analysis must also take into account the broader economic context in which negotiations take place. In other words, the momentum of international negotiations is contingent upon them taking place in a favourable context, which in the case of climate change is largely informed by the evolution of the oil price and the influence of the sustainable economic sector. Higher oil prices tend to stimulate interest in renewable energy policies, while the expansion of sustainable industries increases the opportunity costs of reversing to carbon-intensive modes of production.

The index created by combining the oil spot price and the Dow Jones Sustainability World Index (DJSWI) is shown in Fig 2 and offers a rather sober view regarding the short term future of climate negotiations. The tremendous pressure of the global financial crisis in 2008-2009 broke the momentum of climate negotiations at COP 15 in Copenhagen (first red arrow). The economic context has steadily improved afterwards (green arrow), but it seems to enter a slight period of retraction (second red arrow), which might not bode well for the immediate future of climate negotiations.

To conclude, COP 21 does qualify as a negotiation breakthrough because its outcome has substantially exceeded the parties’ expectations about what needs to be accomplished in order to address the climate change crisis. What is less clear is whether COP 22 in Marrakech in November 2016 will be able to build on COP21’s momentum and continue its positive agenda. The collapse of the oil price in the past year has introduced a negative pressure point in the broader context of the negotiations, which the sustainability economic sector might not be able to offset.

About the Author: Corneliu Bjola is Associate Professor in Diplomatic Studies at the University of Oxford. His research interests lie at the intersection of diplomatic studies, negotiation theory, international ethics, and crisis management. He has authored or edited five books, including the recent co-edited volumes on Secret Diplomacy: Concepts, Contexts and Cases (2016) and Digital Diplomacy: Theory and Practice (2015). His work has been published in the European Journal of International Relations, International Negotiation, Review of International Studies, British Journal of Politics and International Relations, Global Policy, Journal of Global Ethics and The Hague Journal of Diplomacy. Bjola is Co-Editor of the book series on “New Diplomatic Studies” with Routledge and Editor-in-Chief of the new journal “Diplomacy and Foreign Policy” with Brill.

To conclude, COP 21 does qualify as a negotiation breakthrough because its outcome has substantially exceeded the parties’ expectations about what needs to be accomplished in order to address the climate change crisis. What is less clear is whether COP 22 in Marrakech in November 2016 will be able to build on COP21’s momentum and continue its positive agenda. The collapse of the oil price in the past year has introduced a negative pressure point in the broader context of the negotiations, which the sustainability economic sector might not be able to offset.

About the Author: Corneliu Bjola is Associate Professor in Diplomatic Studies at the University of Oxford. His research interests lie at the intersection of diplomatic studies, negotiation theory, international ethics, and crisis management. He has authored or edited five books, including the recent co-edited volumes on Secret Diplomacy: Concepts, Contexts and Cases (2016) and Digital Diplomacy: Theory and Practice (2015). His work has been published in the European Journal of International Relations, International Negotiation, Review of International Studies, British Journal of Politics and International Relations, Global Policy, Journal of Global Ethics and The Hague Journal of Diplomacy. Bjola is Co-Editor of the book series on “New Diplomatic Studies” with Routledge and Editor-in-Chief of the new journal “Diplomacy and Foreign Policy” with Brill.

What Fig 1 is not able to tell us is whether the COP 21 breakthrough is sustainable that is, whether we should expect climate negotiations to continue on the current positive trend or they would likely reverse to a zig-zag or negative pattern. As I’ve argued elsewhere, the sustainability of a negotiation breakthrough cannot be predicted using data pertaining only to negotiation outcomes. The analysis must also take into account the broader economic context in which negotiations take place. In other words, the momentum of international negotiations is contingent upon them taking place in a favourable context, which in the case of climate change is largely informed by the evolution of the oil price and the influence of the sustainable economic sector. Higher oil prices tend to stimulate interest in renewable energy policies, while the expansion of sustainable industries increases the opportunity costs of reversing to carbon-intensive modes of production.

The index created by combining the oil spot price and the Dow Jones Sustainability World Index (DJSWI) is shown in Fig 2 and offers a rather sober view regarding the short term future of climate negotiations. The tremendous pressure of the global financial crisis in 2008-2009 broke the momentum of climate negotiations at COP 15 in Copenhagen (first red arrow). The economic context has steadily improved afterwards (green arrow), but it seems to enter a slight period of retraction (second red arrow), which might not bode well for the immediate future of climate negotiations.

What Fig 1 is not able to tell us is whether the COP 21 breakthrough is sustainable that is, whether we should expect climate negotiations to continue on the current positive trend or they would likely reverse to a zig-zag or negative pattern. As I’ve argued elsewhere, the sustainability of a negotiation breakthrough cannot be predicted using data pertaining only to negotiation outcomes. The analysis must also take into account the broader economic context in which negotiations take place. In other words, the momentum of international negotiations is contingent upon them taking place in a favourable context, which in the case of climate change is largely informed by the evolution of the oil price and the influence of the sustainable economic sector. Higher oil prices tend to stimulate interest in renewable energy policies, while the expansion of sustainable industries increases the opportunity costs of reversing to carbon-intensive modes of production.

The index created by combining the oil spot price and the Dow Jones Sustainability World Index (DJSWI) is shown in Fig 2 and offers a rather sober view regarding the short term future of climate negotiations. The tremendous pressure of the global financial crisis in 2008-2009 broke the momentum of climate negotiations at COP 15 in Copenhagen (first red arrow). The economic context has steadily improved afterwards (green arrow), but it seems to enter a slight period of retraction (second red arrow), which might not bode well for the immediate future of climate negotiations.

To conclude, COP 21 does qualify as a negotiation breakthrough because its outcome has substantially exceeded the parties’ expectations about what needs to be accomplished in order to address the climate change crisis. What is less clear is whether COP 22 in Marrakech in November 2016 will be able to build on COP21’s momentum and continue its positive agenda. The collapse of the oil price in the past year has introduced a negative pressure point in the broader context of the negotiations, which the sustainability economic sector might not be able to offset.

About the Author: Corneliu Bjola is Associate Professor in Diplomatic Studies at the University of Oxford. His research interests lie at the intersection of diplomatic studies, negotiation theory, international ethics, and crisis management. He has authored or edited five books, including the recent co-edited volumes on Secret Diplomacy: Concepts, Contexts and Cases (2016) and Digital Diplomacy: Theory and Practice (2015). His work has been published in the European Journal of International Relations, International Negotiation, Review of International Studies, British Journal of Politics and International Relations, Global Policy, Journal of Global Ethics and The Hague Journal of Diplomacy. Bjola is Co-Editor of the book series on “New Diplomatic Studies” with Routledge and Editor-in-Chief of the new journal “Diplomacy and Foreign Policy” with Brill.

To conclude, COP 21 does qualify as a negotiation breakthrough because its outcome has substantially exceeded the parties’ expectations about what needs to be accomplished in order to address the climate change crisis. What is less clear is whether COP 22 in Marrakech in November 2016 will be able to build on COP21’s momentum and continue its positive agenda. The collapse of the oil price in the past year has introduced a negative pressure point in the broader context of the negotiations, which the sustainability economic sector might not be able to offset.

About the Author: Corneliu Bjola is Associate Professor in Diplomatic Studies at the University of Oxford. His research interests lie at the intersection of diplomatic studies, negotiation theory, international ethics, and crisis management. He has authored or edited five books, including the recent co-edited volumes on Secret Diplomacy: Concepts, Contexts and Cases (2016) and Digital Diplomacy: Theory and Practice (2015). His work has been published in the European Journal of International Relations, International Negotiation, Review of International Studies, British Journal of Politics and International Relations, Global Policy, Journal of Global Ethics and The Hague Journal of Diplomacy. Bjola is Co-Editor of the book series on “New Diplomatic Studies” with Routledge and Editor-in-Chief of the new journal “Diplomacy and Foreign Policy” with Brill.

The views presented in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of any other organization.