.

We are seeing a fundamental shift in the transformation of cities. There is a conscious move away from implementing point solutions that address the most visible pain points to a much broader approach that adopts a solutions portfolio to deliver fundamental outcomes for citizens, communities and businesses. In a world that is being buffeted by turbulence and uncertainty, enhancing city resilience has become a major area of focus.

Rockefeller Foundation’s 100 Resilient Cities defines resilience as “the capacity of cities to function, so that the people living and working in cities – particularly the poor and the vulnerable – survive and thrive no matter what stresses or shocks they encounter.” Benson defines social resilience as “the ability to withstand, recover from, and reorganize in response to crises so that all members of society may develop or maintain the ability to thrive”. It is interesting to note the common thread running through these two definitions of resilience is a focus on people, especially the poor, elderly and the vulnerable.

A closer look reveals that crises are not even-handed as far as the impact on people is concerned. In Hurricane Katrina, more than 70% of the people who perished were aged above 60. Close to 50% of the fatalities from Superstorm Sandy were people 65 or older. In The Great East Japan Earthquake of 2011, more than two-thirds of those who lost their lives were over 60 years old. Other vulnerable segments experience impacts that are disproportionate in scale. The Institute for Women’s Policy Research (IWPR), in a 2010 policy document, noted that since poorer women have less “mobility and access to resources”, they are more vulnerable in natural disasters. Data shows that sexual assault rates in Mississippi rose from 4.6 to 16.3 per 100,000 per day, a year after Hurricane Katrina, partly because many women were forced to leave their homes and live in shelters. In the spate of floods in cities in Asia, the poor (and the elderly poor) have suffered the most. The impact on the elderly, the poor, the disadvantaged has been devastating.

There are multiple reasons for this disparity in impact, including:

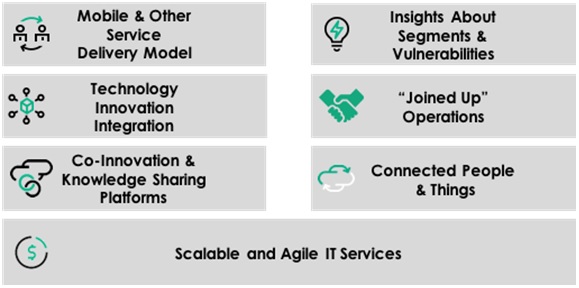

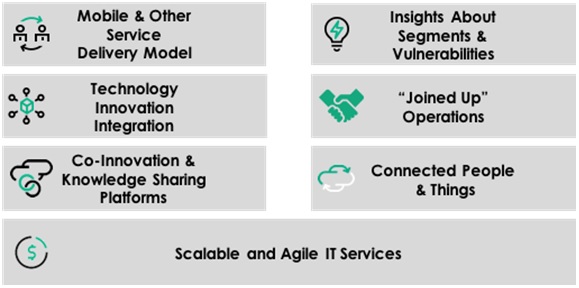

This architecture would:

This architecture would:

- Illness and restricted mobility

- Physical and social isolation – the elderly often live alone

- Location – the elderly or the poor often live in the most vulnerable areas as property prices in these locations are the cheapest

- Disabilities and health conditions: In Japan during the earthquake, those with dementia were too disoriented to evacuate. Often, those impacted are left in conditions with insufficient food, water, exposed to heat or cold, and sometimes without life-saving drugs – conditions that place vulnerable segments, the elderly and the young, at grave risk.

- Gaining a deep understanding of the demographic makeup of a city and identifying citizen segments and any specific vulnerabilities. ASTDR’s Social Vulnerability Index provides an excellent framework for planners and public health officials to identify and map communities in the US that will most likely need support during a crisis. Similar mapping efforts, even highly simplified ones, would be extremely valuable in cities across the world.

- Sponsoring and supporting co-creation and co-innovation efforts where citizens and communities become key participants in finding solutions that enhance resilience. Ibasho Café in Japan came into being after the earthquake in 2011. Here the elderly lead resilience efforts and it is an excellent example of citizen and community engagement. Ibasho Café is built around a set of fundamental concepts that enhance resilience including empowering the elderly, community formation, physical and social infrastructure and knowledge sharing.

- Using information technology to gain deep insights into citizens, their vulnerabilities and risks. Information and communication technology also becomes a powerful tool in the innovation and delivery of new services to citizens.

This architecture would:

This architecture would:

- Provide deep insights about the citizen base, their demographic profile, location, vulnerabilities and risks from service disruptions. These insights help make more informed decisions ranging from policy to budget and resource allocation as well as crafting specific response interventions in times of crisis.

- Create and enable new, agile processes that develop and nurture communities, craft solutions from a bottom-up approach and create alternate pathways. HPE’s Social Innovation Platform enables citizens to participate in co-creating new solution in a matter of weeks.

- Develop multiple ways of reaching citizens and create multi-agency, “wrap around” services that are geared towards the specific needs of vulnerable population segments.

- Allow citizens to form their own support networks so that they become “first responders”. In the case of displaced women, why not create a “Facebook” analog so that these highly vulnerable women can form their own mutually supportive network? To bridge the digital divide, the needed smart phones could easily come from donations.

- Create knowledge repository and share experiences, lessons learned and forming a network that would span multiple cities. It is very interesting to see the knowledge sharing that is taking place between Ibasho Café and other disaster affected areas such as Nepal, the Philippines and Indonesia.

- Incubate and adopt new technology advances to deliver services in new and innovative ways. For example, developing countries have begun using drones to deliver vaccines and critical medical supplies to remote areas. Why not use the same technology to deliver critical life-support medicines to those impacted during times of crises?

The views presented in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of any other organization.

a global affairs media network

Social Resilience: Information Technology as a Disruptive Enabler

Skyline of a city made of circuit board structure skyscrapers, with a cirucit board graphics background||

September 14, 2016

We are seeing a fundamental shift in the transformation of cities. There is a conscious move away from implementing point solutions that address the most visible pain points to a much broader approach that adopts a solutions portfolio to deliver fundamental outcomes for citizens, communities and businesses. In a world that is being buffeted by turbulence and uncertainty, enhancing city resilience has become a major area of focus.

Rockefeller Foundation’s 100 Resilient Cities defines resilience as “the capacity of cities to function, so that the people living and working in cities – particularly the poor and the vulnerable – survive and thrive no matter what stresses or shocks they encounter.” Benson defines social resilience as “the ability to withstand, recover from, and reorganize in response to crises so that all members of society may develop or maintain the ability to thrive”. It is interesting to note the common thread running through these two definitions of resilience is a focus on people, especially the poor, elderly and the vulnerable.

A closer look reveals that crises are not even-handed as far as the impact on people is concerned. In Hurricane Katrina, more than 70% of the people who perished were aged above 60. Close to 50% of the fatalities from Superstorm Sandy were people 65 or older. In The Great East Japan Earthquake of 2011, more than two-thirds of those who lost their lives were over 60 years old. Other vulnerable segments experience impacts that are disproportionate in scale. The Institute for Women’s Policy Research (IWPR), in a 2010 policy document, noted that since poorer women have less “mobility and access to resources”, they are more vulnerable in natural disasters. Data shows that sexual assault rates in Mississippi rose from 4.6 to 16.3 per 100,000 per day, a year after Hurricane Katrina, partly because many women were forced to leave their homes and live in shelters. In the spate of floods in cities in Asia, the poor (and the elderly poor) have suffered the most. The impact on the elderly, the poor, the disadvantaged has been devastating.

There are multiple reasons for this disparity in impact, including:

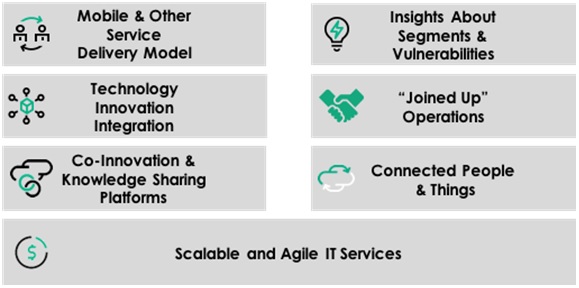

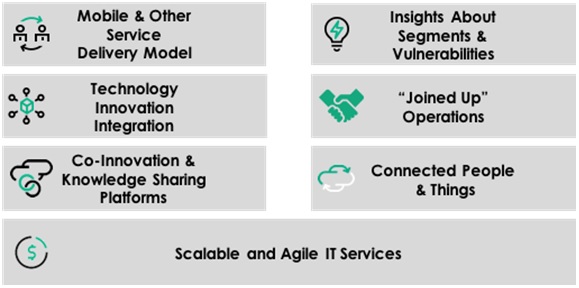

This architecture would:

This architecture would:

- Illness and restricted mobility

- Physical and social isolation – the elderly often live alone

- Location – the elderly or the poor often live in the most vulnerable areas as property prices in these locations are the cheapest

- Disabilities and health conditions: In Japan during the earthquake, those with dementia were too disoriented to evacuate. Often, those impacted are left in conditions with insufficient food, water, exposed to heat or cold, and sometimes without life-saving drugs – conditions that place vulnerable segments, the elderly and the young, at grave risk.

- Gaining a deep understanding of the demographic makeup of a city and identifying citizen segments and any specific vulnerabilities. ASTDR’s Social Vulnerability Index provides an excellent framework for planners and public health officials to identify and map communities in the US that will most likely need support during a crisis. Similar mapping efforts, even highly simplified ones, would be extremely valuable in cities across the world.

- Sponsoring and supporting co-creation and co-innovation efforts where citizens and communities become key participants in finding solutions that enhance resilience. Ibasho Café in Japan came into being after the earthquake in 2011. Here the elderly lead resilience efforts and it is an excellent example of citizen and community engagement. Ibasho Café is built around a set of fundamental concepts that enhance resilience including empowering the elderly, community formation, physical and social infrastructure and knowledge sharing.

- Using information technology to gain deep insights into citizens, their vulnerabilities and risks. Information and communication technology also becomes a powerful tool in the innovation and delivery of new services to citizens.

This architecture would:

This architecture would:

- Provide deep insights about the citizen base, their demographic profile, location, vulnerabilities and risks from service disruptions. These insights help make more informed decisions ranging from policy to budget and resource allocation as well as crafting specific response interventions in times of crisis.

- Create and enable new, agile processes that develop and nurture communities, craft solutions from a bottom-up approach and create alternate pathways. HPE’s Social Innovation Platform enables citizens to participate in co-creating new solution in a matter of weeks.

- Develop multiple ways of reaching citizens and create multi-agency, “wrap around” services that are geared towards the specific needs of vulnerable population segments.

- Allow citizens to form their own support networks so that they become “first responders”. In the case of displaced women, why not create a “Facebook” analog so that these highly vulnerable women can form their own mutually supportive network? To bridge the digital divide, the needed smart phones could easily come from donations.

- Create knowledge repository and share experiences, lessons learned and forming a network that would span multiple cities. It is very interesting to see the knowledge sharing that is taking place between Ibasho Café and other disaster affected areas such as Nepal, the Philippines and Indonesia.

- Incubate and adopt new technology advances to deliver services in new and innovative ways. For example, developing countries have begun using drones to deliver vaccines and critical medical supplies to remote areas. Why not use the same technology to deliver critical life-support medicines to those impacted during times of crises?

The views presented in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of any other organization.