After the financial crisis of 2008, the United States, Europe, and many other nations around the world began to debate austerity measures in order to reduce their stock of sovereign debt. One sector considered for reduction was healthcare expenditures. Critics of this approach argued that a reduction in healthcare expenditures would reduce the quality of life for people in that country. Shortly after the crisis, the World Health Organization (WHO), argued for direct investment in healthcare as a means of improving the quality of life.

According to Director-General of the World Health Organization, Dr. Margaret Chan, in 2009: “Health is a global concern. It is a vital investment in economic development and poverty reduction. It is central to the achievement of the Millennium Development Goals. Access to health care is a fundamental entitlement and responsibility of governments the world over… Progress in one direction depends on all the others. We compromise on any one of these elements at our collective peril.”

Quantity of government health expenditures is often debated by legislatures around the world. The rhetoric from countries around the world after the financial crisis makes this a particularly interesting variable to analyze efficacy, especially in relation to a variable that it is designed to lengthen, like life expectancy. The question then emerges as to which is more relevant for health policy in countries around the world. If our goal is to improve health outcomes around the world, should we be investing in the growth of income per capita or should we be investing more directly to enhance healthcare expenditures by the government?

Life expectancy is a popular measure for quality of life in any given country. In 1975, economist and sociologist Dr. Samuel Preston published a landmark paper examining the relationship between life expectancy and per capita GDP. The relationship forms a logarithmic curve, which famously became called ‘the Preston Curve.’ The following is the original image from his 1975 paper:

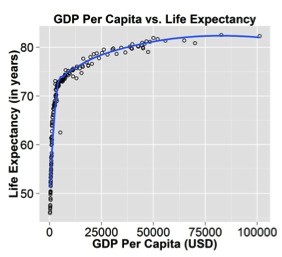

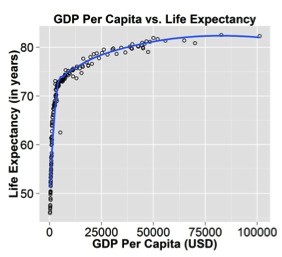

Interestingly, public data available from the World Bank and AidData shows that relationship still holds true for the past decade. That is, GDP per capita still follows the same logarithmic relationship to life expectancy as it did in the early to mid-20th century. The direction of causality remains unclear. Does higher life expectancy lead to greater national income per capita or does greater national income per capita lead to longer life expectancy? The following curve was generated from data across 175 different countries across all income groups:

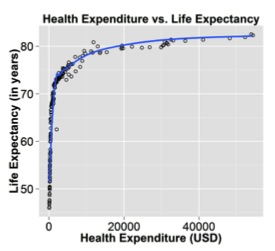

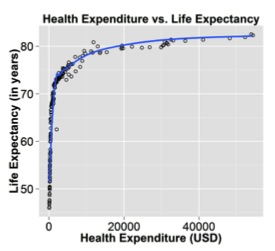

This graph suggests that Dr. Preston’s analysis is still relevant for the contemporary time period. This mathematical relationship also appears when examining life expectancy against government health expenditure per capita, shown below:

GDP per capita and health expenditure by the government follow the same logarithmic pattern associated with an increase in life expectancy. The correlation shows that additional dollar inputs suffer from diminishing marginal returns on life expectancy. The poorer the country, the more pronounced the effects of increasing GDP per capita on life expectancy. As the country becomes richer, the effect is less pronounced, but still viable. This suggests that there are effective natural constraints on increasing individual life expectancy. While the logarithmic function has technically infinite potential, it becomes impractical to continue investing the necessary resources with the intent to increase life expectancy beyond a certain point. Interestingly, OECD members tend to have higher base life expectancies. It may be worth examining the characteristics that these nations have over those nations who are not members. It appears that higher life expectancy is a positive byproduct of an increase in GDP per capita and a strengthening of characteristics held by OECD countries.

In the multivariable linear regression, GDP per capita and OECD membership, as a measure of civil society, reduce the effect of government health expenditure per capita to a non-significant number in comparison to the robust effects of the other two variables. The two significant variables were controlled for their obvious correlation to one another. This is interesting but it does not automatically discount the impact of government health expenditure on the lengthening of life expectancy, but rather it shows that the other two variables are more powerful predictors. It is clear that healthcare expenditure by the government does not have a pronounced effect on life expectancy and that GDP per capita is a more relevant predictor. National investment in economic growth as a means of increasing GDP per capita may still be the best way to approach development aid across the world if the end goal is increasing the length and quality of life of the citizenry. The regression analysis suggests that for every additional 1000 USD increase in GDP per capita there is a predicted average increase of about half a year in life expectancy for any given country.

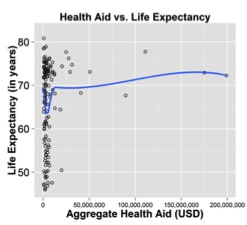

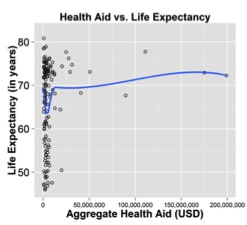

A 2005 article by Dr. Raghuram Rajan at the International Monetary Fund (IMF) calls into question the effectiveness of aid in general. According to him, “…for aid to be effective in the future, the aid apparatus (in terms of how aid should be delivered, to whom, in what form, and under what conditions) will have to be rethought.” He finds that aid in general lacks a robust relationship to growth. The regression analysis between targeted health aid and life expectancy show a similar relationship with a variable relevant to what health aid specifically is trying to fix.

Sven Wilson in a 2011 article in the journal World Development examined a similar relationship using infant mortality rates and a number of other indicators as a measure of health. “DAH [development assistance for health] dollars move strongly towards countries with declining mortality, but they do not generate it.” The correlation above does not show that health aid is ineffective but rather, much in the same vein as Wilson’s findings flows strongly towards countries with lower life expectancies. Unfortunately the fact remains clear from these data and from Dr. Wilson’s findings that “DAH spending from 1975 to 2005 had no discernible effect on country-level mortality rates in high mortality countries.”

This definitely calls for a deeper examination of what we are actually trying to accomplish in the developing world with our money. Are we really improving the quality of life for the people in these countries or are our efforts an exercise in futility?

Perhaps we should reexamine Dr. Margaret Chan’s call to invest directly into healthcare as a way of avoiding our “collective peril” and approach the problem from a more holistic and less sector-specific development approach. Perhaps the answer cannot be approached solely from a development-aid perspective, but a joint plan of aid followed by reciprocal economic activity between developing countries and the developed world. The development rhetoric around health aid packages or healthcare expenditure by the government is often filled with optimistic messages and hopeful desires for a future devoid of infectious disease and infant mortality, but applying band-aids to flesh wounds rarely fixes the root cause of the problem. The reality is that the data suggest that sustained economic growth in poor regions around the world will save, extend, and improve more lives moving into the 21st century.

This article was originally published in the Diplomatic Courier's July/August 2014 print edition.

a global affairs media network

Life Expectancy in the Developing World: How Do We Buy Longer Lives?

August 7, 2014

After the financial crisis of 2008, the United States, Europe, and many other nations around the world began to debate austerity measures in order to reduce their stock of sovereign debt. One sector considered for reduction was healthcare expenditures. Critics of this approach argued that a reduction in healthcare expenditures would reduce the quality of life for people in that country. Shortly after the crisis, the World Health Organization (WHO), argued for direct investment in healthcare as a means of improving the quality of life.

According to Director-General of the World Health Organization, Dr. Margaret Chan, in 2009: “Health is a global concern. It is a vital investment in economic development and poverty reduction. It is central to the achievement of the Millennium Development Goals. Access to health care is a fundamental entitlement and responsibility of governments the world over… Progress in one direction depends on all the others. We compromise on any one of these elements at our collective peril.”

Quantity of government health expenditures is often debated by legislatures around the world. The rhetoric from countries around the world after the financial crisis makes this a particularly interesting variable to analyze efficacy, especially in relation to a variable that it is designed to lengthen, like life expectancy. The question then emerges as to which is more relevant for health policy in countries around the world. If our goal is to improve health outcomes around the world, should we be investing in the growth of income per capita or should we be investing more directly to enhance healthcare expenditures by the government?

Life expectancy is a popular measure for quality of life in any given country. In 1975, economist and sociologist Dr. Samuel Preston published a landmark paper examining the relationship between life expectancy and per capita GDP. The relationship forms a logarithmic curve, which famously became called ‘the Preston Curve.’ The following is the original image from his 1975 paper:

Interestingly, public data available from the World Bank and AidData shows that relationship still holds true for the past decade. That is, GDP per capita still follows the same logarithmic relationship to life expectancy as it did in the early to mid-20th century. The direction of causality remains unclear. Does higher life expectancy lead to greater national income per capita or does greater national income per capita lead to longer life expectancy? The following curve was generated from data across 175 different countries across all income groups:

This graph suggests that Dr. Preston’s analysis is still relevant for the contemporary time period. This mathematical relationship also appears when examining life expectancy against government health expenditure per capita, shown below:

GDP per capita and health expenditure by the government follow the same logarithmic pattern associated with an increase in life expectancy. The correlation shows that additional dollar inputs suffer from diminishing marginal returns on life expectancy. The poorer the country, the more pronounced the effects of increasing GDP per capita on life expectancy. As the country becomes richer, the effect is less pronounced, but still viable. This suggests that there are effective natural constraints on increasing individual life expectancy. While the logarithmic function has technically infinite potential, it becomes impractical to continue investing the necessary resources with the intent to increase life expectancy beyond a certain point. Interestingly, OECD members tend to have higher base life expectancies. It may be worth examining the characteristics that these nations have over those nations who are not members. It appears that higher life expectancy is a positive byproduct of an increase in GDP per capita and a strengthening of characteristics held by OECD countries.

In the multivariable linear regression, GDP per capita and OECD membership, as a measure of civil society, reduce the effect of government health expenditure per capita to a non-significant number in comparison to the robust effects of the other two variables. The two significant variables were controlled for their obvious correlation to one another. This is interesting but it does not automatically discount the impact of government health expenditure on the lengthening of life expectancy, but rather it shows that the other two variables are more powerful predictors. It is clear that healthcare expenditure by the government does not have a pronounced effect on life expectancy and that GDP per capita is a more relevant predictor. National investment in economic growth as a means of increasing GDP per capita may still be the best way to approach development aid across the world if the end goal is increasing the length and quality of life of the citizenry. The regression analysis suggests that for every additional 1000 USD increase in GDP per capita there is a predicted average increase of about half a year in life expectancy for any given country.

A 2005 article by Dr. Raghuram Rajan at the International Monetary Fund (IMF) calls into question the effectiveness of aid in general. According to him, “…for aid to be effective in the future, the aid apparatus (in terms of how aid should be delivered, to whom, in what form, and under what conditions) will have to be rethought.” He finds that aid in general lacks a robust relationship to growth. The regression analysis between targeted health aid and life expectancy show a similar relationship with a variable relevant to what health aid specifically is trying to fix.

Sven Wilson in a 2011 article in the journal World Development examined a similar relationship using infant mortality rates and a number of other indicators as a measure of health. “DAH [development assistance for health] dollars move strongly towards countries with declining mortality, but they do not generate it.” The correlation above does not show that health aid is ineffective but rather, much in the same vein as Wilson’s findings flows strongly towards countries with lower life expectancies. Unfortunately the fact remains clear from these data and from Dr. Wilson’s findings that “DAH spending from 1975 to 2005 had no discernible effect on country-level mortality rates in high mortality countries.”

This definitely calls for a deeper examination of what we are actually trying to accomplish in the developing world with our money. Are we really improving the quality of life for the people in these countries or are our efforts an exercise in futility?

Perhaps we should reexamine Dr. Margaret Chan’s call to invest directly into healthcare as a way of avoiding our “collective peril” and approach the problem from a more holistic and less sector-specific development approach. Perhaps the answer cannot be approached solely from a development-aid perspective, but a joint plan of aid followed by reciprocal economic activity between developing countries and the developed world. The development rhetoric around health aid packages or healthcare expenditure by the government is often filled with optimistic messages and hopeful desires for a future devoid of infectious disease and infant mortality, but applying band-aids to flesh wounds rarely fixes the root cause of the problem. The reality is that the data suggest that sustained economic growth in poor regions around the world will save, extend, and improve more lives moving into the 21st century.

This article was originally published in the Diplomatic Courier's July/August 2014 print edition.