.

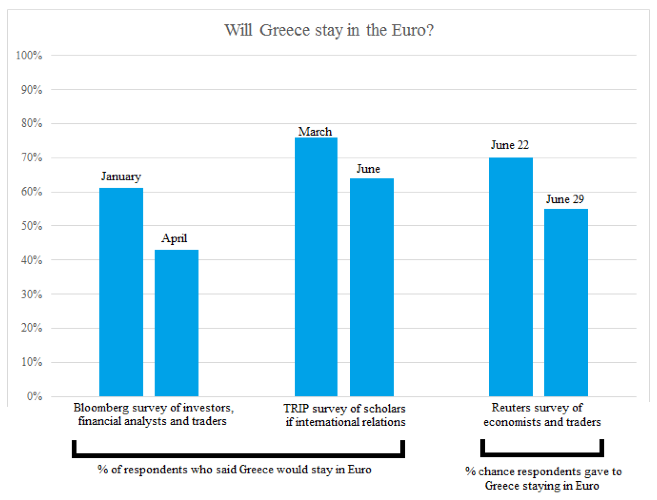

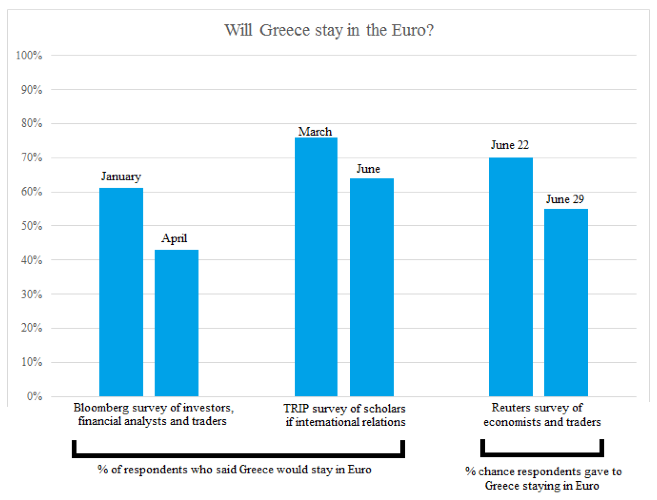

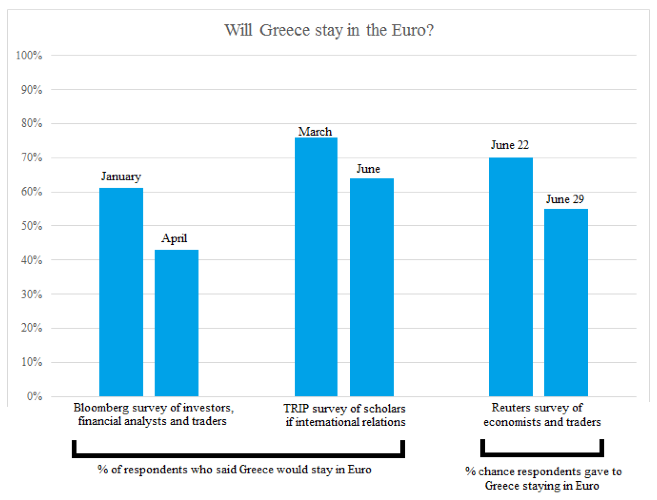

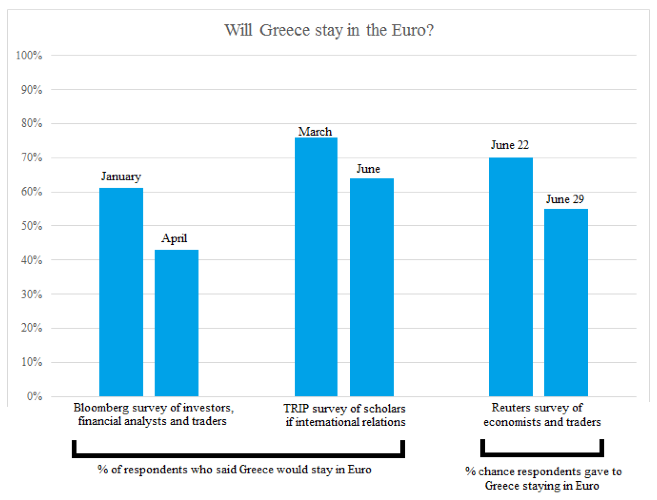

Despite the emergence of a potential deal between Greece and its creditors, the nation is still in precarious shape: another large payment is due to the European Central Bank on July 20. Surveys reveal that experts across fields have revised their opinions of whether Greece will stay in the Euro: Bloomberg polls of financial experts, a Reuters poll of economists, and a poll of international relations (IR) scholars by the Teaching, Research, and International Policy (TRIP) project at the College of William and Mary all show declining optimism over the country’s chances to stay in the single currency.

What motivated the change in attitudes (besides the turbulent political series of events)? Barry Eichengreen, an economist from UC Berkeley, attributes the general decline in optimism to an earlier underestimation of what motivated the key players – politics guided their actions more than economics. With regard to the greater confidence amongst IR scholars, it may reflect Daniel Drezner’s point that political scientists view the Eurozone crisis not as a unique flashpoint but as a structural issue – a strength test of political institutions. Based on their academic focus, these scholars may put greater faith in institutions such as the European Central Bank, the IMF, and the European Union as a whole.

Would a Grexit be bad for Greece?

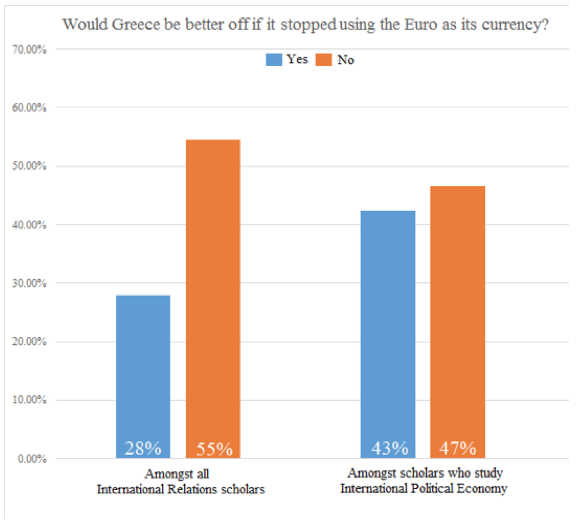

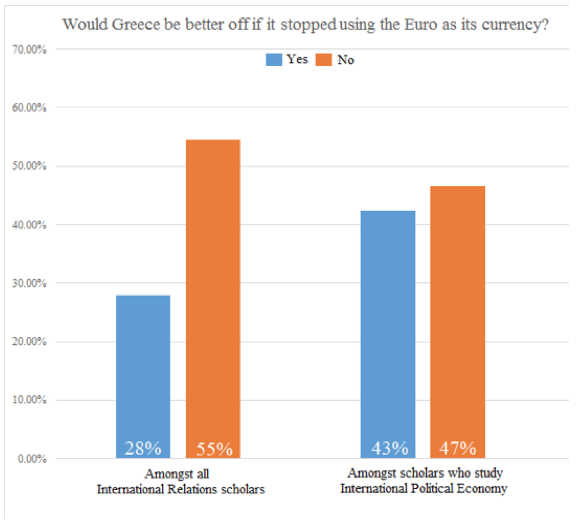

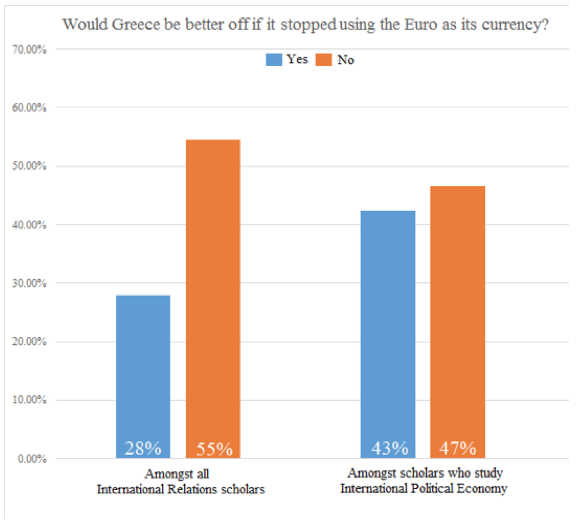

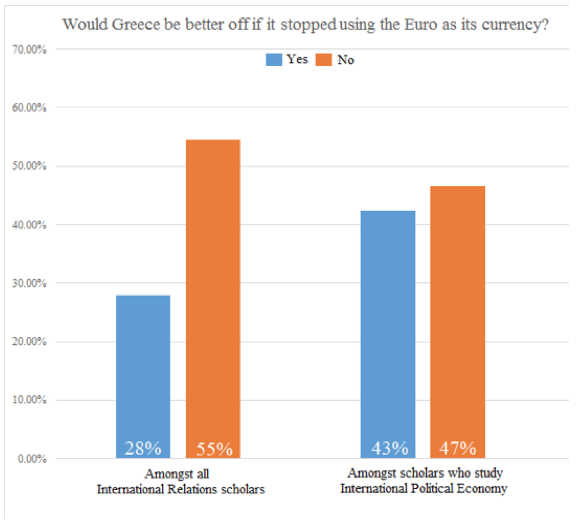

A related (and possibly more important) question is whether a Grexit would be bad for the economy and society of Greece compared to the alternative of reform, further austerity, and staying in the Eurozone. Only 28 percent of IR scholars would consider a Greek exit from the euro to be good for Greece while nearly twice that number see it as a negative outcome. However, among those whose primary field of study is international political economy (IPE), the issue area most closely related to the Eurozone crisis, only 47 percent see a Grexit scenario as negative, with 43 percent considering it positive.

Why this optimism? There are a few structural reasons that IPE scholars may oppose the Euro (or at least a country’s individual decision to stay in it) on face. The nature of international economics constrains countries to an “impossible trinity” where they can choose only two of the following: an independent monetary policy, a stable foreign exchange rate and the free movement of capital. Two potential objections arise from this so-called “trilemma.” The first is that, without an ability to devalue a nominal exchange rate with the rest of Europe (since independent monetary policy is surrendered to the European Central Bank), Greece is forced to resort to internal devaluation through austerity to increase its economic competitiveness. The second theoretical problem is that Greece’s responses to the crisis of confidence short-ends them in the trilemma. Rather than picking two, Athens’s necessary capital controls to prevent bank-runs (which is simultaneously necessary given market expectations but also runs against the spirit of the European Union’s “fourth freedom” of free movement of capital) essentially renders them in the short-term with only a stable exchange rate at the expense of the other parts of the trinity. Regarding these points, Paul Krugman and Joseph Stiglitz both have commented that a Grexit could be liberating for the Greek economy – economic policy pursued from Athens, rather than Brussels or Berlin, may be more responsive to Greek needs. Political economists who place value in either independent monetary policy or the necessity of the ability for capital controls may view Greece’s continued existence in the Eurozone as harmful to either of these goals.

What motivated the change in attitudes (besides the turbulent political series of events)? Barry Eichengreen, an economist from UC Berkeley, attributes the general decline in optimism to an earlier underestimation of what motivated the key players – politics guided their actions more than economics. With regard to the greater confidence amongst IR scholars, it may reflect Daniel Drezner’s point that political scientists view the Eurozone crisis not as a unique flashpoint but as a structural issue – a strength test of political institutions. Based on their academic focus, these scholars may put greater faith in institutions such as the European Central Bank, the IMF, and the European Union as a whole.

Would a Grexit be bad for Greece?

A related (and possibly more important) question is whether a Grexit would be bad for the economy and society of Greece compared to the alternative of reform, further austerity, and staying in the Eurozone. Only 28 percent of IR scholars would consider a Greek exit from the euro to be good for Greece while nearly twice that number see it as a negative outcome. However, among those whose primary field of study is international political economy (IPE), the issue area most closely related to the Eurozone crisis, only 47 percent see a Grexit scenario as negative, with 43 percent considering it positive.

Why this optimism? There are a few structural reasons that IPE scholars may oppose the Euro (or at least a country’s individual decision to stay in it) on face. The nature of international economics constrains countries to an “impossible trinity” where they can choose only two of the following: an independent monetary policy, a stable foreign exchange rate and the free movement of capital. Two potential objections arise from this so-called “trilemma.” The first is that, without an ability to devalue a nominal exchange rate with the rest of Europe (since independent monetary policy is surrendered to the European Central Bank), Greece is forced to resort to internal devaluation through austerity to increase its economic competitiveness. The second theoretical problem is that Greece’s responses to the crisis of confidence short-ends them in the trilemma. Rather than picking two, Athens’s necessary capital controls to prevent bank-runs (which is simultaneously necessary given market expectations but also runs against the spirit of the European Union’s “fourth freedom” of free movement of capital) essentially renders them in the short-term with only a stable exchange rate at the expense of the other parts of the trinity. Regarding these points, Paul Krugman and Joseph Stiglitz both have commented that a Grexit could be liberating for the Greek economy – economic policy pursued from Athens, rather than Brussels or Berlin, may be more responsive to Greek needs. Political economists who place value in either independent monetary policy or the necessity of the ability for capital controls may view Greece’s continued existence in the Eurozone as harmful to either of these goals.

With these dissents about whether a “Grexit” would be bad, why do so many scholars still bet against Athens deciding to withdraw? And why might IR scholars be more confident than financial analysts? The TRIP data produces a caveat on the entire debate by illustrating a correlation between views on the positivity of a Grexit and its likelihood. Among IR scholars who believe Greece would lose from leaving the Eurozone, 77 percent believe Greece will stay within it. On the other hand, only 50 percent of those who believe a Grexit would be beneficial think Greece will keep the euro. This raises the possibility that a significant number of scholars assume policymakers are working toward “sensible” economic ends, and then base their expectations on what they see as a positive outcome. This finding presents predictions of the Eurozone, at least of IR scholars, as not a function of recent and changing financial events but a structural debate as to whether the concept of the Euro is good for member-states. Those who find reasons to oppose may very well believe Greece will eventually come to the same conclusion (such as many IPE scholars) while the majority still believe in the positivity of the common currency and thus predict that Greece will eventually “come around.” Prime Minister Tsipras’s recent willingness to compromise may be evidence of the latter.

Ultimately, while many still retain confidence in Greece remaining in the Eurozone, there remains divisions on whether that is a good thing. Growing pessimism among IR scholars mirrors financial analysts and economics but is more gradual. This is most likely due to the framing of the Greek issue as a singular political question of whether the Euro is positive and whether institutions are equipped to handle the crisis rather than reactions to changing financial events.

With these dissents about whether a “Grexit” would be bad, why do so many scholars still bet against Athens deciding to withdraw? And why might IR scholars be more confident than financial analysts? The TRIP data produces a caveat on the entire debate by illustrating a correlation between views on the positivity of a Grexit and its likelihood. Among IR scholars who believe Greece would lose from leaving the Eurozone, 77 percent believe Greece will stay within it. On the other hand, only 50 percent of those who believe a Grexit would be beneficial think Greece will keep the euro. This raises the possibility that a significant number of scholars assume policymakers are working toward “sensible” economic ends, and then base their expectations on what they see as a positive outcome. This finding presents predictions of the Eurozone, at least of IR scholars, as not a function of recent and changing financial events but a structural debate as to whether the concept of the Euro is good for member-states. Those who find reasons to oppose may very well believe Greece will eventually come to the same conclusion (such as many IPE scholars) while the majority still believe in the positivity of the common currency and thus predict that Greece will eventually “come around.” Prime Minister Tsipras’s recent willingness to compromise may be evidence of the latter.

Ultimately, while many still retain confidence in Greece remaining in the Eurozone, there remains divisions on whether that is a good thing. Growing pessimism among IR scholars mirrors financial analysts and economics but is more gradual. This is most likely due to the framing of the Greek issue as a singular political question of whether the Euro is positive and whether institutions are equipped to handle the crisis rather than reactions to changing financial events.

What motivated the change in attitudes (besides the turbulent political series of events)? Barry Eichengreen, an economist from UC Berkeley, attributes the general decline in optimism to an earlier underestimation of what motivated the key players – politics guided their actions more than economics. With regard to the greater confidence amongst IR scholars, it may reflect Daniel Drezner’s point that political scientists view the Eurozone crisis not as a unique flashpoint but as a structural issue – a strength test of political institutions. Based on their academic focus, these scholars may put greater faith in institutions such as the European Central Bank, the IMF, and the European Union as a whole.

Would a Grexit be bad for Greece?

A related (and possibly more important) question is whether a Grexit would be bad for the economy and society of Greece compared to the alternative of reform, further austerity, and staying in the Eurozone. Only 28 percent of IR scholars would consider a Greek exit from the euro to be good for Greece while nearly twice that number see it as a negative outcome. However, among those whose primary field of study is international political economy (IPE), the issue area most closely related to the Eurozone crisis, only 47 percent see a Grexit scenario as negative, with 43 percent considering it positive.

Why this optimism? There are a few structural reasons that IPE scholars may oppose the Euro (or at least a country’s individual decision to stay in it) on face. The nature of international economics constrains countries to an “impossible trinity” where they can choose only two of the following: an independent monetary policy, a stable foreign exchange rate and the free movement of capital. Two potential objections arise from this so-called “trilemma.” The first is that, without an ability to devalue a nominal exchange rate with the rest of Europe (since independent monetary policy is surrendered to the European Central Bank), Greece is forced to resort to internal devaluation through austerity to increase its economic competitiveness. The second theoretical problem is that Greece’s responses to the crisis of confidence short-ends them in the trilemma. Rather than picking two, Athens’s necessary capital controls to prevent bank-runs (which is simultaneously necessary given market expectations but also runs against the spirit of the European Union’s “fourth freedom” of free movement of capital) essentially renders them in the short-term with only a stable exchange rate at the expense of the other parts of the trinity. Regarding these points, Paul Krugman and Joseph Stiglitz both have commented that a Grexit could be liberating for the Greek economy – economic policy pursued from Athens, rather than Brussels or Berlin, may be more responsive to Greek needs. Political economists who place value in either independent monetary policy or the necessity of the ability for capital controls may view Greece’s continued existence in the Eurozone as harmful to either of these goals.

What motivated the change in attitudes (besides the turbulent political series of events)? Barry Eichengreen, an economist from UC Berkeley, attributes the general decline in optimism to an earlier underestimation of what motivated the key players – politics guided their actions more than economics. With regard to the greater confidence amongst IR scholars, it may reflect Daniel Drezner’s point that political scientists view the Eurozone crisis not as a unique flashpoint but as a structural issue – a strength test of political institutions. Based on their academic focus, these scholars may put greater faith in institutions such as the European Central Bank, the IMF, and the European Union as a whole.

Would a Grexit be bad for Greece?

A related (and possibly more important) question is whether a Grexit would be bad for the economy and society of Greece compared to the alternative of reform, further austerity, and staying in the Eurozone. Only 28 percent of IR scholars would consider a Greek exit from the euro to be good for Greece while nearly twice that number see it as a negative outcome. However, among those whose primary field of study is international political economy (IPE), the issue area most closely related to the Eurozone crisis, only 47 percent see a Grexit scenario as negative, with 43 percent considering it positive.

Why this optimism? There are a few structural reasons that IPE scholars may oppose the Euro (or at least a country’s individual decision to stay in it) on face. The nature of international economics constrains countries to an “impossible trinity” where they can choose only two of the following: an independent monetary policy, a stable foreign exchange rate and the free movement of capital. Two potential objections arise from this so-called “trilemma.” The first is that, without an ability to devalue a nominal exchange rate with the rest of Europe (since independent monetary policy is surrendered to the European Central Bank), Greece is forced to resort to internal devaluation through austerity to increase its economic competitiveness. The second theoretical problem is that Greece’s responses to the crisis of confidence short-ends them in the trilemma. Rather than picking two, Athens’s necessary capital controls to prevent bank-runs (which is simultaneously necessary given market expectations but also runs against the spirit of the European Union’s “fourth freedom” of free movement of capital) essentially renders them in the short-term with only a stable exchange rate at the expense of the other parts of the trinity. Regarding these points, Paul Krugman and Joseph Stiglitz both have commented that a Grexit could be liberating for the Greek economy – economic policy pursued from Athens, rather than Brussels or Berlin, may be more responsive to Greek needs. Political economists who place value in either independent monetary policy or the necessity of the ability for capital controls may view Greece’s continued existence in the Eurozone as harmful to either of these goals.

With these dissents about whether a “Grexit” would be bad, why do so many scholars still bet against Athens deciding to withdraw? And why might IR scholars be more confident than financial analysts? The TRIP data produces a caveat on the entire debate by illustrating a correlation between views on the positivity of a Grexit and its likelihood. Among IR scholars who believe Greece would lose from leaving the Eurozone, 77 percent believe Greece will stay within it. On the other hand, only 50 percent of those who believe a Grexit would be beneficial think Greece will keep the euro. This raises the possibility that a significant number of scholars assume policymakers are working toward “sensible” economic ends, and then base their expectations on what they see as a positive outcome. This finding presents predictions of the Eurozone, at least of IR scholars, as not a function of recent and changing financial events but a structural debate as to whether the concept of the Euro is good for member-states. Those who find reasons to oppose may very well believe Greece will eventually come to the same conclusion (such as many IPE scholars) while the majority still believe in the positivity of the common currency and thus predict that Greece will eventually “come around.” Prime Minister Tsipras’s recent willingness to compromise may be evidence of the latter.

Ultimately, while many still retain confidence in Greece remaining in the Eurozone, there remains divisions on whether that is a good thing. Growing pessimism among IR scholars mirrors financial analysts and economics but is more gradual. This is most likely due to the framing of the Greek issue as a singular political question of whether the Euro is positive and whether institutions are equipped to handle the crisis rather than reactions to changing financial events.

With these dissents about whether a “Grexit” would be bad, why do so many scholars still bet against Athens deciding to withdraw? And why might IR scholars be more confident than financial analysts? The TRIP data produces a caveat on the entire debate by illustrating a correlation between views on the positivity of a Grexit and its likelihood. Among IR scholars who believe Greece would lose from leaving the Eurozone, 77 percent believe Greece will stay within it. On the other hand, only 50 percent of those who believe a Grexit would be beneficial think Greece will keep the euro. This raises the possibility that a significant number of scholars assume policymakers are working toward “sensible” economic ends, and then base their expectations on what they see as a positive outcome. This finding presents predictions of the Eurozone, at least of IR scholars, as not a function of recent and changing financial events but a structural debate as to whether the concept of the Euro is good for member-states. Those who find reasons to oppose may very well believe Greece will eventually come to the same conclusion (such as many IPE scholars) while the majority still believe in the positivity of the common currency and thus predict that Greece will eventually “come around.” Prime Minister Tsipras’s recent willingness to compromise may be evidence of the latter.

Ultimately, while many still retain confidence in Greece remaining in the Eurozone, there remains divisions on whether that is a good thing. Growing pessimism among IR scholars mirrors financial analysts and economics but is more gradual. This is most likely due to the framing of the Greek issue as a singular political question of whether the Euro is positive and whether institutions are equipped to handle the crisis rather than reactions to changing financial events.The views presented in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of any other organization.

a global affairs media network

Experts Fret About Grexit, But Should They?

||

July 2, 2015

Despite the emergence of a potential deal between Greece and its creditors, the nation is still in precarious shape: another large payment is due to the European Central Bank on July 20. Surveys reveal that experts across fields have revised their opinions of whether Greece will stay in the Euro: Bloomberg polls of financial experts, a Reuters poll of economists, and a poll of international relations (IR) scholars by the Teaching, Research, and International Policy (TRIP) project at the College of William and Mary all show declining optimism over the country’s chances to stay in the single currency.

What motivated the change in attitudes (besides the turbulent political series of events)? Barry Eichengreen, an economist from UC Berkeley, attributes the general decline in optimism to an earlier underestimation of what motivated the key players – politics guided their actions more than economics. With regard to the greater confidence amongst IR scholars, it may reflect Daniel Drezner’s point that political scientists view the Eurozone crisis not as a unique flashpoint but as a structural issue – a strength test of political institutions. Based on their academic focus, these scholars may put greater faith in institutions such as the European Central Bank, the IMF, and the European Union as a whole.

Would a Grexit be bad for Greece?

A related (and possibly more important) question is whether a Grexit would be bad for the economy and society of Greece compared to the alternative of reform, further austerity, and staying in the Eurozone. Only 28 percent of IR scholars would consider a Greek exit from the euro to be good for Greece while nearly twice that number see it as a negative outcome. However, among those whose primary field of study is international political economy (IPE), the issue area most closely related to the Eurozone crisis, only 47 percent see a Grexit scenario as negative, with 43 percent considering it positive.

Why this optimism? There are a few structural reasons that IPE scholars may oppose the Euro (or at least a country’s individual decision to stay in it) on face. The nature of international economics constrains countries to an “impossible trinity” where they can choose only two of the following: an independent monetary policy, a stable foreign exchange rate and the free movement of capital. Two potential objections arise from this so-called “trilemma.” The first is that, without an ability to devalue a nominal exchange rate with the rest of Europe (since independent monetary policy is surrendered to the European Central Bank), Greece is forced to resort to internal devaluation through austerity to increase its economic competitiveness. The second theoretical problem is that Greece’s responses to the crisis of confidence short-ends them in the trilemma. Rather than picking two, Athens’s necessary capital controls to prevent bank-runs (which is simultaneously necessary given market expectations but also runs against the spirit of the European Union’s “fourth freedom” of free movement of capital) essentially renders them in the short-term with only a stable exchange rate at the expense of the other parts of the trinity. Regarding these points, Paul Krugman and Joseph Stiglitz both have commented that a Grexit could be liberating for the Greek economy – economic policy pursued from Athens, rather than Brussels or Berlin, may be more responsive to Greek needs. Political economists who place value in either independent monetary policy or the necessity of the ability for capital controls may view Greece’s continued existence in the Eurozone as harmful to either of these goals.

What motivated the change in attitudes (besides the turbulent political series of events)? Barry Eichengreen, an economist from UC Berkeley, attributes the general decline in optimism to an earlier underestimation of what motivated the key players – politics guided their actions more than economics. With regard to the greater confidence amongst IR scholars, it may reflect Daniel Drezner’s point that political scientists view the Eurozone crisis not as a unique flashpoint but as a structural issue – a strength test of political institutions. Based on their academic focus, these scholars may put greater faith in institutions such as the European Central Bank, the IMF, and the European Union as a whole.

Would a Grexit be bad for Greece?

A related (and possibly more important) question is whether a Grexit would be bad for the economy and society of Greece compared to the alternative of reform, further austerity, and staying in the Eurozone. Only 28 percent of IR scholars would consider a Greek exit from the euro to be good for Greece while nearly twice that number see it as a negative outcome. However, among those whose primary field of study is international political economy (IPE), the issue area most closely related to the Eurozone crisis, only 47 percent see a Grexit scenario as negative, with 43 percent considering it positive.

Why this optimism? There are a few structural reasons that IPE scholars may oppose the Euro (or at least a country’s individual decision to stay in it) on face. The nature of international economics constrains countries to an “impossible trinity” where they can choose only two of the following: an independent monetary policy, a stable foreign exchange rate and the free movement of capital. Two potential objections arise from this so-called “trilemma.” The first is that, without an ability to devalue a nominal exchange rate with the rest of Europe (since independent monetary policy is surrendered to the European Central Bank), Greece is forced to resort to internal devaluation through austerity to increase its economic competitiveness. The second theoretical problem is that Greece’s responses to the crisis of confidence short-ends them in the trilemma. Rather than picking two, Athens’s necessary capital controls to prevent bank-runs (which is simultaneously necessary given market expectations but also runs against the spirit of the European Union’s “fourth freedom” of free movement of capital) essentially renders them in the short-term with only a stable exchange rate at the expense of the other parts of the trinity. Regarding these points, Paul Krugman and Joseph Stiglitz both have commented that a Grexit could be liberating for the Greek economy – economic policy pursued from Athens, rather than Brussels or Berlin, may be more responsive to Greek needs. Political economists who place value in either independent monetary policy or the necessity of the ability for capital controls may view Greece’s continued existence in the Eurozone as harmful to either of these goals.

With these dissents about whether a “Grexit” would be bad, why do so many scholars still bet against Athens deciding to withdraw? And why might IR scholars be more confident than financial analysts? The TRIP data produces a caveat on the entire debate by illustrating a correlation between views on the positivity of a Grexit and its likelihood. Among IR scholars who believe Greece would lose from leaving the Eurozone, 77 percent believe Greece will stay within it. On the other hand, only 50 percent of those who believe a Grexit would be beneficial think Greece will keep the euro. This raises the possibility that a significant number of scholars assume policymakers are working toward “sensible” economic ends, and then base their expectations on what they see as a positive outcome. This finding presents predictions of the Eurozone, at least of IR scholars, as not a function of recent and changing financial events but a structural debate as to whether the concept of the Euro is good for member-states. Those who find reasons to oppose may very well believe Greece will eventually come to the same conclusion (such as many IPE scholars) while the majority still believe in the positivity of the common currency and thus predict that Greece will eventually “come around.” Prime Minister Tsipras’s recent willingness to compromise may be evidence of the latter.

Ultimately, while many still retain confidence in Greece remaining in the Eurozone, there remains divisions on whether that is a good thing. Growing pessimism among IR scholars mirrors financial analysts and economics but is more gradual. This is most likely due to the framing of the Greek issue as a singular political question of whether the Euro is positive and whether institutions are equipped to handle the crisis rather than reactions to changing financial events.

With these dissents about whether a “Grexit” would be bad, why do so many scholars still bet against Athens deciding to withdraw? And why might IR scholars be more confident than financial analysts? The TRIP data produces a caveat on the entire debate by illustrating a correlation between views on the positivity of a Grexit and its likelihood. Among IR scholars who believe Greece would lose from leaving the Eurozone, 77 percent believe Greece will stay within it. On the other hand, only 50 percent of those who believe a Grexit would be beneficial think Greece will keep the euro. This raises the possibility that a significant number of scholars assume policymakers are working toward “sensible” economic ends, and then base their expectations on what they see as a positive outcome. This finding presents predictions of the Eurozone, at least of IR scholars, as not a function of recent and changing financial events but a structural debate as to whether the concept of the Euro is good for member-states. Those who find reasons to oppose may very well believe Greece will eventually come to the same conclusion (such as many IPE scholars) while the majority still believe in the positivity of the common currency and thus predict that Greece will eventually “come around.” Prime Minister Tsipras’s recent willingness to compromise may be evidence of the latter.

Ultimately, while many still retain confidence in Greece remaining in the Eurozone, there remains divisions on whether that is a good thing. Growing pessimism among IR scholars mirrors financial analysts and economics but is more gradual. This is most likely due to the framing of the Greek issue as a singular political question of whether the Euro is positive and whether institutions are equipped to handle the crisis rather than reactions to changing financial events.

What motivated the change in attitudes (besides the turbulent political series of events)? Barry Eichengreen, an economist from UC Berkeley, attributes the general decline in optimism to an earlier underestimation of what motivated the key players – politics guided their actions more than economics. With regard to the greater confidence amongst IR scholars, it may reflect Daniel Drezner’s point that political scientists view the Eurozone crisis not as a unique flashpoint but as a structural issue – a strength test of political institutions. Based on their academic focus, these scholars may put greater faith in institutions such as the European Central Bank, the IMF, and the European Union as a whole.

Would a Grexit be bad for Greece?

A related (and possibly more important) question is whether a Grexit would be bad for the economy and society of Greece compared to the alternative of reform, further austerity, and staying in the Eurozone. Only 28 percent of IR scholars would consider a Greek exit from the euro to be good for Greece while nearly twice that number see it as a negative outcome. However, among those whose primary field of study is international political economy (IPE), the issue area most closely related to the Eurozone crisis, only 47 percent see a Grexit scenario as negative, with 43 percent considering it positive.

Why this optimism? There are a few structural reasons that IPE scholars may oppose the Euro (or at least a country’s individual decision to stay in it) on face. The nature of international economics constrains countries to an “impossible trinity” where they can choose only two of the following: an independent monetary policy, a stable foreign exchange rate and the free movement of capital. Two potential objections arise from this so-called “trilemma.” The first is that, without an ability to devalue a nominal exchange rate with the rest of Europe (since independent monetary policy is surrendered to the European Central Bank), Greece is forced to resort to internal devaluation through austerity to increase its economic competitiveness. The second theoretical problem is that Greece’s responses to the crisis of confidence short-ends them in the trilemma. Rather than picking two, Athens’s necessary capital controls to prevent bank-runs (which is simultaneously necessary given market expectations but also runs against the spirit of the European Union’s “fourth freedom” of free movement of capital) essentially renders them in the short-term with only a stable exchange rate at the expense of the other parts of the trinity. Regarding these points, Paul Krugman and Joseph Stiglitz both have commented that a Grexit could be liberating for the Greek economy – economic policy pursued from Athens, rather than Brussels or Berlin, may be more responsive to Greek needs. Political economists who place value in either independent monetary policy or the necessity of the ability for capital controls may view Greece’s continued existence in the Eurozone as harmful to either of these goals.

What motivated the change in attitudes (besides the turbulent political series of events)? Barry Eichengreen, an economist from UC Berkeley, attributes the general decline in optimism to an earlier underestimation of what motivated the key players – politics guided their actions more than economics. With regard to the greater confidence amongst IR scholars, it may reflect Daniel Drezner’s point that political scientists view the Eurozone crisis not as a unique flashpoint but as a structural issue – a strength test of political institutions. Based on their academic focus, these scholars may put greater faith in institutions such as the European Central Bank, the IMF, and the European Union as a whole.

Would a Grexit be bad for Greece?

A related (and possibly more important) question is whether a Grexit would be bad for the economy and society of Greece compared to the alternative of reform, further austerity, and staying in the Eurozone. Only 28 percent of IR scholars would consider a Greek exit from the euro to be good for Greece while nearly twice that number see it as a negative outcome. However, among those whose primary field of study is international political economy (IPE), the issue area most closely related to the Eurozone crisis, only 47 percent see a Grexit scenario as negative, with 43 percent considering it positive.

Why this optimism? There are a few structural reasons that IPE scholars may oppose the Euro (or at least a country’s individual decision to stay in it) on face. The nature of international economics constrains countries to an “impossible trinity” where they can choose only two of the following: an independent monetary policy, a stable foreign exchange rate and the free movement of capital. Two potential objections arise from this so-called “trilemma.” The first is that, without an ability to devalue a nominal exchange rate with the rest of Europe (since independent monetary policy is surrendered to the European Central Bank), Greece is forced to resort to internal devaluation through austerity to increase its economic competitiveness. The second theoretical problem is that Greece’s responses to the crisis of confidence short-ends them in the trilemma. Rather than picking two, Athens’s necessary capital controls to prevent bank-runs (which is simultaneously necessary given market expectations but also runs against the spirit of the European Union’s “fourth freedom” of free movement of capital) essentially renders them in the short-term with only a stable exchange rate at the expense of the other parts of the trinity. Regarding these points, Paul Krugman and Joseph Stiglitz both have commented that a Grexit could be liberating for the Greek economy – economic policy pursued from Athens, rather than Brussels or Berlin, may be more responsive to Greek needs. Political economists who place value in either independent monetary policy or the necessity of the ability for capital controls may view Greece’s continued existence in the Eurozone as harmful to either of these goals.

With these dissents about whether a “Grexit” would be bad, why do so many scholars still bet against Athens deciding to withdraw? And why might IR scholars be more confident than financial analysts? The TRIP data produces a caveat on the entire debate by illustrating a correlation between views on the positivity of a Grexit and its likelihood. Among IR scholars who believe Greece would lose from leaving the Eurozone, 77 percent believe Greece will stay within it. On the other hand, only 50 percent of those who believe a Grexit would be beneficial think Greece will keep the euro. This raises the possibility that a significant number of scholars assume policymakers are working toward “sensible” economic ends, and then base their expectations on what they see as a positive outcome. This finding presents predictions of the Eurozone, at least of IR scholars, as not a function of recent and changing financial events but a structural debate as to whether the concept of the Euro is good for member-states. Those who find reasons to oppose may very well believe Greece will eventually come to the same conclusion (such as many IPE scholars) while the majority still believe in the positivity of the common currency and thus predict that Greece will eventually “come around.” Prime Minister Tsipras’s recent willingness to compromise may be evidence of the latter.

Ultimately, while many still retain confidence in Greece remaining in the Eurozone, there remains divisions on whether that is a good thing. Growing pessimism among IR scholars mirrors financial analysts and economics but is more gradual. This is most likely due to the framing of the Greek issue as a singular political question of whether the Euro is positive and whether institutions are equipped to handle the crisis rather than reactions to changing financial events.

With these dissents about whether a “Grexit” would be bad, why do so many scholars still bet against Athens deciding to withdraw? And why might IR scholars be more confident than financial analysts? The TRIP data produces a caveat on the entire debate by illustrating a correlation between views on the positivity of a Grexit and its likelihood. Among IR scholars who believe Greece would lose from leaving the Eurozone, 77 percent believe Greece will stay within it. On the other hand, only 50 percent of those who believe a Grexit would be beneficial think Greece will keep the euro. This raises the possibility that a significant number of scholars assume policymakers are working toward “sensible” economic ends, and then base their expectations on what they see as a positive outcome. This finding presents predictions of the Eurozone, at least of IR scholars, as not a function of recent and changing financial events but a structural debate as to whether the concept of the Euro is good for member-states. Those who find reasons to oppose may very well believe Greece will eventually come to the same conclusion (such as many IPE scholars) while the majority still believe in the positivity of the common currency and thus predict that Greece will eventually “come around.” Prime Minister Tsipras’s recent willingness to compromise may be evidence of the latter.

Ultimately, while many still retain confidence in Greece remaining in the Eurozone, there remains divisions on whether that is a good thing. Growing pessimism among IR scholars mirrors financial analysts and economics but is more gradual. This is most likely due to the framing of the Greek issue as a singular political question of whether the Euro is positive and whether institutions are equipped to handle the crisis rather than reactions to changing financial events.The views presented in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of any other organization.